The Conscious Community Network and Local Food Ecosystem, Chapter 7 Part 2

The Next Step – A Local Food Systems Network… Identifying Our Super-Connectors and “Multiple Stakeholders”… Building Our Network-Centric Ecosystem

Welcome to the Birthing the Symbiotic Age Book!

NEW here? — please visit the TABLE OF CONTENTS FIRST and catch up!

You are in Chapter 7, Part 2, The Next Step – A Local Food Systems Network… Identifying Our Super-Connectors and “Multiple Stakeholders”… Building Our Network-Centric Ecosystem

Chapter 7 posts:

Are you trying to figure out where this is All Going? Read an overview of the Symbiotic Culture Strategy, which embodies the Transcendent through the nodes of intersection within local, grassroots-empowered community networks.

Voice-overs are now at the top of my posts for anyone who doesn’t have the time to sit and read! Also, find this chapter post and all previous posts as podcast episodes on

Spotify and Apple!

Previously, at the end of Chapter 7, Part 1

As I suggested in the introduction, historians Arnold Toynbee and Oswald Spengler agreed that the epitaph on the grave of every fallen empire is the same:

Died of spiritual and moral decline!

Toynbee states a sign of decline is the growing gap between the haves and the have-nots. When society focuses primarily on material possessions and the pursuit of comfort and self-interest, when citizens and organizations care more about their ego needs than that of the community, the gap widens, and society breaks down. Toynbee maintained that it was more a spiritual than an economic issue.

He wrote that when people stopped caring for one another, this was a sign of “moral decline.” Hence, the epitaph. This has happened repeatedly, and the result is a world that is broken and sick at heart.

Yet, despite being surrounded on all sides by this all-pervasive Culture of Separation, our group in Reno empowered a “conscious community network”– a parallel functional system operating alongside the failing dysfunctional one. Even though we still operated inside the Culture of Separation—we had to because that’s where “reality” lives—we were also independent of it — we were in it but not “of” it.

In this “parallel reality,” our Conscious Community Network was focused on the Virtues and making the world “right-side” up by focusing on creating a local cultural change strategy — a Culture of Connection — and this desire to serve the entire community brought us to our next step.

Chapter 7, Part 2

The Conscious Community Network and Local Food Ecosystem -

The Next Step – A Local Food Systems Network

With our three foundational goals—build a Cooperative Community, Strengthen our Local Economy, and Practice Living more Consciously—we were ready to grow the Conscious Community Network. We had no specific project yet, but there was a sense that it would involve food.

So, at one meeting in 2005, someone proposed, “Why don’t we have a community garden?”

I was very resistant to this idea, although I didn’t fully realize why then. It was a bit puzzling to me. Opposing a community garden project seemed akin to being “against” motherhood, apple pie, or kittens! However, I soon began to understand my objections, which concerned what a symbiotic network is and does. Let’s say we agreed and then began to put our energy into this garden. And then another community member came along and said, “And, yes. Now we need to open a restaurant.” And so on.

Before too long, we would lose the contextual purpose of being a symbiotic network. Our energy would be going toward one more worthy endeavor, in competition with every other worthy endeavor in the community.

We would be managing projects instead of focusing on our unique purpose—to be a supportive, regenerative network that would uplift every other valuable enterprise and organization in our community.

And, we would have created just another silo — another competing project — unwittingly reinforcing the Culture of Separation.

The symbiotic network is a catalyst providing network connectivity and coordination, a place and space where people connect with each other and share resources instead of managing separate projects. Such a new community weaving context would be able to support dozens of sub-projects launched by our community members in collaboration.

This is exactly what happened, as you will see.

Other than the model of the Sarvodaya movement, what we were doing in Reno was totally unique. Our singular purpose was to connect people and leaders across the silos of separation. And although we didn’t realize it then, we were bucking a 3,000-year-old trend! While civilization was “busy” collapsing, we discovered a way to rise beyond the conflict by having a shared set of Virtues and principles, a set of identified community needs, a gentle network container, and a common purpose.

To reiterate a point I’ve made before and will make again, we went past the well-intentioned programs that mediate conflict through conversations and dialogues between “warring” tribes. We stepped entirely off this battlefield onto a new “playing field,” collaborating beyond differences to address our common issues. In fact, we very likely made these dialogues unnecessary because we created a practical, living example of mutual understanding and mutual benefit.

The benefits of collaboration made themselves obvious!

Even with this clarity, our community network still had to address the question, “What’s next?” The community garden idea was on the right track because people realized our next step involved food. But how?

I had the “aha” that led to the Northern Nevada Local Food System Network at a meeting of a local interfaith group. The existing Interfaith Network, which we will discuss in the next chapter, was an aligned project.

The Interfaith Network held two luncheons a year, each inviting a faith leader from the community to speak. This event was held at a huge and elegant local home, and sitting next to me was the stake president of the local Latter-day Saints (Mormon) church. At the time, Northern Nevada had the third-largest LDS population in the country—some 40,000 members.

Like most Mormon leaders, he was a layman and, in fact, my dentist. We were discussing the Mormon practice of emergency preparation, including food storage. Farmers grow and then dehydrate food as part of their tradition, making it perfect for long-term storage.

They have been preparing for “societal breakdown” for decades; emergency food storage is key. I wondered if Reno could do this, ensuring ample food was stored in case of an environmental or human-made disaster. If possible, it could then be done in other regions, nationally, and even globally.

That’s when I realized that what was needed was a local food network that would connect and support local growers, retailers, and others — a natural spinoff from our successful Local Living Economy network. Over the years in Reno, many people have expressed a need to strengthen the local food system.

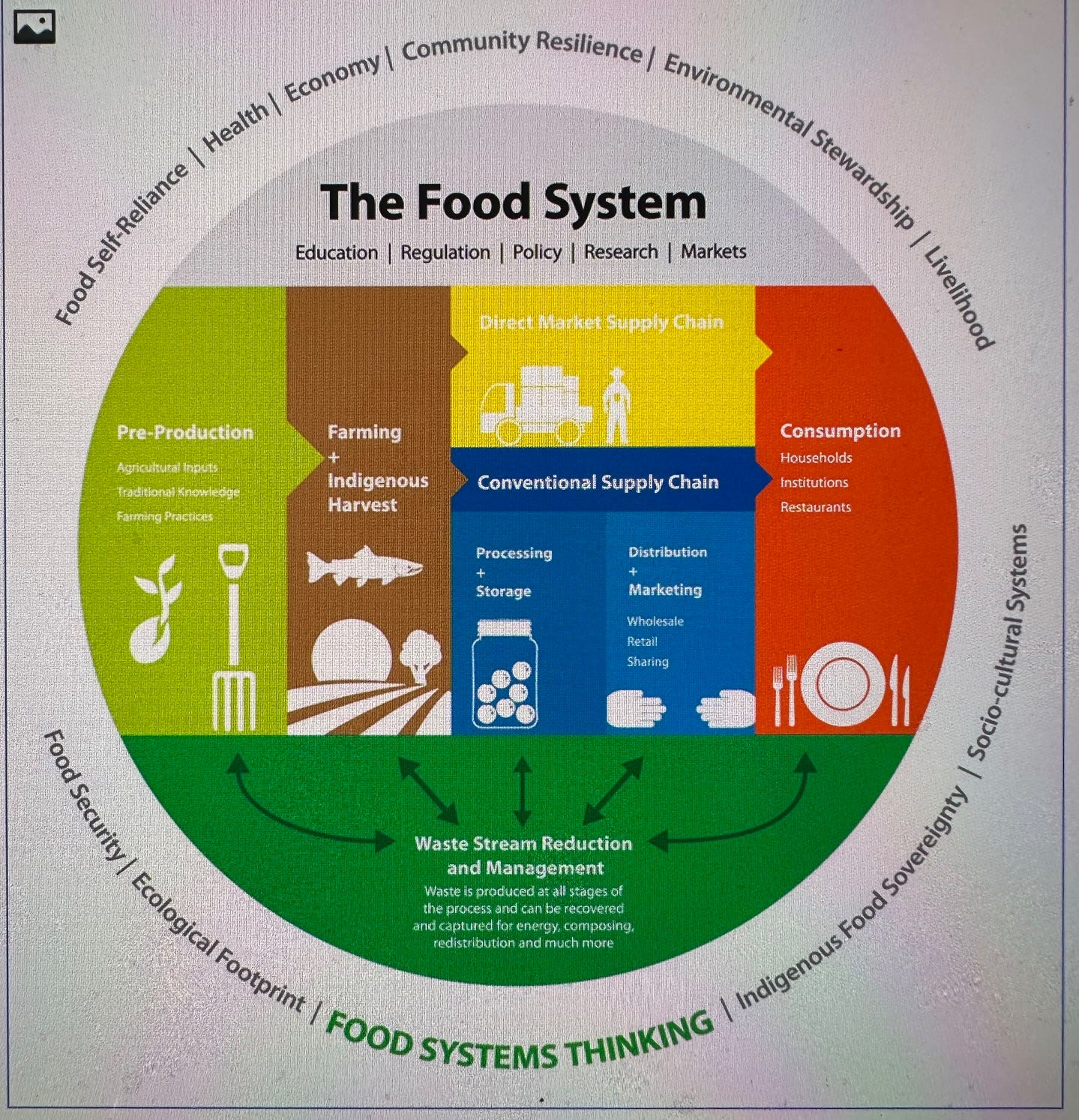

A Local Food System Network would be a regenerative AND market-based approach to increasing local farm, ranch, and value-added food production and local food consumption. It would involve mapping and connecting all elements of a food system into a coherent marketplace to help our region become increasingly self-sufficient.

Identifying Our Super-Connectors/Multiple Stakeholders

It was the Fall of 2005, and through our strong small business and community connections, we surveyed and mapped the super-connectors in the local food system. They included farmers and ranchers, farmer’s markets, backyard farmers, food cooperatives, local/organic food enthusiasts, “foodies, “ending hunger” advocates, activists, grocers, institutional food buyers, and restaurateurs.

I personally called six individuals we identified as food super-connectors. The first call was to the owner of one of the oldest farms (112 years old) in the nearby region of Fallon, Nevada. His family has been farming for five generations! We’d already had a connection through our Buy Local movement. He was also a small business counselor for a local economic development organization, so he, too, was a networker.

When we got on the line, I asked him, “What do you think about forming a local food system network?” His answer was telling and showed the challenge of forming these networks—his answer was, “I’m already doing it!”

“I’m already doing it!”

I was curious what he meant. Was there already a Local Food System Network in Northern Nevada that I didn’t know about? As a symbiotic network catalyst, convener, and weaver, I had no judgment, just curiosity. So, I asked him to describe his network. “Pretend you are an eagle flying over your network,” I said, “seeing how you fit into the total food system.”

He told me his existing food network consisted mostly of local food producers (farmers and ranchers) like himself. I asked if he was selling his produce in retail farmer’s markets, and he said no. I asked if he participated in Community-Supportive Agriculture (CSAs, direct-to-family subscription farming), and he said no. Selling farm-to-table (farm-to-restaurant)? The answer was no.

It turned out that his farm produced a huge amount of a few crops sold outside the community. He was a wholesaler and had hardly any direct sales connections to the urban areas of Reno.

What he was describing wasn’t the whole Local Food System Network (there wasn’t one at the time), but one of many large clusters making up the whole food system, not the totality of connections. The larger, more established idea of a Local Food System Network includes all the “clusters” he mentioned and then some, literally every business, organization, or network involved in growing, buying, distributing, preparing, and serving food.

I saw it as a way to regenerate local farming and, in the process, bring financial and ecological benefits to the entire northern Nevada community. It required no outside funding source and no government permission or direction.

It was a Virtuous, market-based approach to increasing local farm/ranch and value-added food production and sparking consumer awareness and consumption of locally grown food.

You could think of this as a broader regional economy sub-sector network.

After listening to him describe his business and its limitations in terms of local impact, I asked him, “Would you be interested in meeting with other connectors and super-connectors like yourself to discuss the need for a larger local food system network?”

And he said, “Yeah.”

After our 30-minute conversation, we had our first “buy-in.”

The next step was for me to connect with other local food “stakeholders” who were also connectors and super-connectors, and before any group meeting, help them understand what this network would be and get their buy-in as well. These stakeholders included many individuals, businesses, nonprofit organizations, and local governments that were already part of our Conscious Community Network.

As I had done with the early adopter farmer, I spoke to these identified connectors, one by one, explaining the concept behind our local food network — to support the many endeavors that already comprised the local food system — and enrolling them in the idea.

These original super-connectors included the leader of a regional farmer’s market network, an individual involved with food cooperatives, someone else whose field was food security, a well-connected restauranteur, and a few others.

Let me reiterate why bringing multiple stakeholders together before a larger community meeting was so important. Building a successful buy-local network indeed made it easier for these stakeholders, catalysts, and connectors to say yes. Still, because of the persistence of the “taker” culture, it took more patient explanation about how this symbiotic food network would be different from the forms people were already familiar with, like coalitions—an old-paradigm concept based on organizations aligning to “get” something.

The symbiotic network is based on what I mentioned at the end of Chapter 6 -“Gratuitousness,” where the operative question is, “What can I give?” This may seem insignificant, but a coalition is generally ad hoc cooperation around a specific issue. Once that issue is resolved, every organization goes back to being a self-absorbed, “single-cell organism,” a silo focused on self-preservation and competition.

The symbiotic network is entirely different. It is an “on-growing,” enduring network of cooperation that continues to enhance the economic (and spiritual) well-being of the entire community, even as individual businesses and organizations continue

to “compete” in the marketplace.

As an aside, in his book Cradle to Cradle, William McDonough reminds us that the original Greek definition of competition was “to strive together.” It wasn’t about defeating or dominating other competitors but improving one’s own game. In this regard, our symbiotic network was “competitive” in the best sense!

This is not the understanding of competition that dominates our Western worldview, where it either consciously or subconsciously comes down to me OR you. Our buy local network was successful because it introduced a radically new idea—me AND you—and that experience allowed our key stakeholders and connectors to see above and beyond the system as it already was.

As I said at the beginning of this chapter, we were riding this unfamiliar wave of a “positive” culture, the joy of participating in something that benefits all.

When word got out that we were considering a Local Food System Network, we did get offers from more than one nonprofit to “run it.” I had to patiently explain that this network was an autonomous “nonformal organization” rather than a pet project of an already-existing organization, which would make it just another competing silo.

Building Our Network-Centric Food Ecosystem

The term I have come to use to describe symbiotic networks is “scaffolding.”

Scaffolding is not the building itself but the network-centric structure that allows it to be built. If the structure we want to build is a thriving, cooperative, local food economy, then our symbiotic network is what brings all the elements together to facilitate the cooperation, collaboration, and communication necessary.

We call this scaffolding structure an “ecosystem” because, like the mycelial web we discussed in Section I, all sorts of community “nutrients” can circulate and be exchanged through this living, connected system.

As we will see, such networks can be activated around food and other community concerns, such as health, education, arts and culture, neighborhoods, etc.

Back to the story!

It was only after I had the foundational support of key super-connectors who grasped the concept and were enthusiastic about it that we gathered in person. Imagine, in contrast, simply calling a community meeting of fifty to a hundred stakeholders to present the idea. We would have had dozens of individuals, each with their own questions and concerns, and the result would have been pushback, conflict, and energy drain.

One key lesson I learned in building a symbiotic community is to secure the foundation by handling the major questions and objections in these individual conversations before group meetings or public presentations.

So, when we convened our first small meeting of half a dozen super-connectors, we could focus on spiritual alignment of intention on mutual benefit rather than selling or explaining the concept. In the individual conversations, we had already unpacked all the potential misconceptions. We discussed forming this network together in our first face-to-face meeting, which took about an hour.

We addressed what I call “frozen assets” inside a community — untapped value and “potentiality” kept in place by the old system of competition and the siloed structure that discourages people from sharing key contacts or information. A symbiotic network starts with trust and generosity — generously sharing your Rolodex!

Each of the key stakeholders/connectors in the room already had their own network “cluster” of colleagues in different arenas of the food growing, distribution, advocacy, and sales domains. Imagine what energy could be released in the community when these clusters are interconnected.

We then asked each person in the room to write down all their “downline” business connections. Through these six people’s networks alone, we expanded the playing field for our food network to almost one hundred organizations and the fifty thousand people they were connected to!

Something else that is unique and significant about such a symbiotic network is that all the participant leaders come together equally around the same table and have equal control, so there is no ego about one person or group being in control over others.

Initially, the catalyst is a “single” hub and spoke network. The novelty here is that when the first small group meets, even the initial catalyst is not above anyone. Instead, the catalyst takes its place in a circle representing a distributed network of co-equal stakeholders.

This contrasts with the situation when an existing organization launches a network, reinforcing that one organization still controls the network. Human nature, being what it is, is territorial and tribal, and other community leaders generally see a network formed by another organization as competitive.

A Symbiotic Network is not a separate organization. Instead, it is a community-wide, multi-hub, network-centric ecosystem — really an “organism” — where power is shared by the stakeholders. Because the dominant system of siloed organization is so pervasive and so “invisible” – that is, we mistake it for the “only” organizational reality that is possible – I want to reiterate how our symbiotic network ecosystem is unique:

It’s a virtuous, purpose-based network for mutual benefit, where participants ask, “What can I give?” It's not a fixed coalition where each organization only wants to “get” something.

It’s a unique “umbrella” or “meta-network” designed to enhance the work and provide tangible benefit to each member organization and the whole community – not just another competing silo.

It’s a completely independent network, not controlled by an existing non-profit, business, or local government.

It’s an informal consortium that connects and proliferates the good in a region in one or more multiple domains (e.g., around food, education, health care, neighborhoods, arts and culture)—not a formal organization with a formal board of directors, executive director, CEO, employees, and budget.

The network’s “essential” quality (its developmental process) is even more important than the structure. It rests on the foundation of the Ancient Blueprint and practice of the Virtues.

Without that, it would just be “building the road.” The Virtues ensure that the “road builds us” – that we develop and cultivate the inner resources to hold the space for mutual benefit above and beyond whatever divides us.

So, Maslow’s “highest” need of actualization is not something to be attained but something foundational—to have a community that cooperates and collaborates, you need people capable of cooperating and collaborating. To “hold space” for community, you already need to be a UNITER and not an unwitting DIVIDER!

Something else I want to reiterate about our network and why it worked. We were “radically inclusive”.

Just as our buy local campaign included all local businesses, not just those that were “organic,” “regenerative,” or “green,” we wanted to ensure the road we were building included every food-related enterprise that wanted to participate — including conventional ones.

In this new playing field of mutual regard and trust, where people talk, interact, and learn from each other, change can happen “organically” and by considering basic market forces.

As we will learn in more detail later, the “early adopter” farmer we referred to earlier in this chapter – who initially had a completely conventional operation – later went organic and became one of the area’s largest producers — after seeing the demand that our network helped create.

Find out how we discovered a Cultural Change Strategy in the NEXT POST — Chapter 7, Part 3: Going “Public” and Gaining Momentum… “Shortening the Path” – Our Social Media BEFORE Social Media…Local, Cultural Change Strategy – Why Paradise DID NOT Get Paved?

PREVIOUS POST

TABLE OF CONTENTS

NEXT POST

https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#inbox/FMfcgzGxTNtnKsgtSKcXcPplctfHDXGX

Dear Richard,

Thank you so much for this, your most recent contribution, which provided me with good ideas about reaching each prospective participant individually before the first forum/roundtable. I will include that in my approach.

I have several years of experience organizing public forums around the subject of antinuclear weapons proliferation, which bimonthly forums our chapter of five members planned, and which I promoted. I had intended for those interested in realizing DESO to read the content before coming together over it. However, the idea of one-to-one introduction to the content for decentralization would be most useful prior to gathering at the first roundtable.

Then, your ideas about generating generosity from local, “networked,” conventional producers is good, and can be integrated among prospects for the start up organization of decentralized economic social organization, DESO.

DESO needs Land and components for the small holdings it is composed of.

Richard writes, “It’s a virtuous, purpose-based network for mutual benefit, where participants ask, “What can I give?”” That impetus is expected in DESO. However, DESO includes much more than that. Richard, you mentioned Maslow, and self-actualization, which in DESO with communal, community support is expected of each person from birth. The culture of decentralized civilization is grounded upon economic mutualism. Economic mutualism only functions while the decentralized civilization in question is matricentric, and that too is a structured proposition. (1)

Richard, I thank you for your kind contribution, and I look forward to your next chapter.

You be well and be in Good Spirits!

Yours always, Reed Kinney

Note, 1: Women’s Revolution, by Abdullah Ocalan

https://www.freeocalan.org/books/downloads/EN-brochure_liberating-life-womans-revolution_2017.pdf