The Conscious Community Network and Local Food Ecosystem, Chapter 7 Part 3

Going “Public” and Gaining Momentum… “Shortening the Path” – Our Social Media BEFORE Social Media… Fractal Community Empowerment… Local, Cultural Change Strategy – Why Paradise DID NOT Get Paved?

Welcome to the Birthing the Symbiotic Age Book!

NEW here? — please visit the TABLE OF CONTENTS FIRST and catch up!

You are in Chapter 7, Part 3, Going “Public” and Gaining Momentum… “Shortening the Path” – Our Social Media BEFORE Social Media… Fractal Community Empowerment… Local, Cultural Change Strategy – Why Paradise DID NOT Get Paved?

Chapter 7 posts:

Going “Public” and Gaining Momentum… “Shortening the Path” – Our Social Media BEFORE Social Media… Local, Cultural Change Strategy – Why Paradise DID NOT Get Paved?

Are you trying to figure out where this is All Going? Read an overview of the Symbiotic Culture Strategy, which embodies the Transcendent through the nodes of intersection within local, grassroots-empowered community networks.

Voice-overs are now at the top of my posts for anyone who doesn’t have the time to sit and read! Also, find this chapter post and all previous posts as podcast episodes on

Spotify and Apple!

Previously, at the end of Chapter 7, Part 2

So, Maslow’s “highest” need of actualization is not something to be attained but something foundational—to have a community that cooperates and collaborates, you need people capable of cooperating and collaborating. To “hold space” for community, you need to be a UNITER, not an unwitting DIVIDER!

Something else I want to reiterate about our network and why it worked.

We were “radically inclusive”. Just as our buy local campaign included all local businesses, not just those that were “organic,” “regenerative,” or “green,” we wanted to ensure the road we were building included every food-related enterprise that wanted to participate — including conventional ones.

In this new playing field of mutual regard and trust, where people talk, interact, and learn from each other, change can happen “organically” and by considering basic market forces.

As we will learn in more detail later, the “early adopter” farmer we referred to earlier in this chapter – who initially had a completely conventional operation – later went organic and became one of the area’s largest producers — after seeing the demand that our network helped create.

Chapter 7, Part 3

The Conscious Community Network and Local Food Ecosystem

Going “Public” and Gaining Momentum

With the buy-in and participation of our initial food super-connector / stakeholders and their agreement to reach out to their networks, we were ready to go public.

Our first meeting was in December 2005 at a locally owned restaurant, where 85 leaders and other interested parties packed the space — it was a standing room only. We went from six leaders/connectors with 50,000 constituents to eighty-five leaders/connectors with 400,000 constituents, touching almost every resident of Washoe County and beyond.

The morning breakfast meeting lasted two hours, and as part of the process, some of our original founding stakeholders stood up and spoke for two minutes about their aspect of the food economy and how they saw this local food network benefitting them and the community at large. Audience members then could also share, offering a response or suggestion. Through this process of sharing, the symbiotic local food network “proved” itself to everyone in the room.

The Washoe County School District's (64,000 students) purchasing director was there to explore buying food from local sources. The Northern Nevada Food Bank director stood up and stated that she had been thinking of the very same idea—of building a broad network around food, especially in eliminating hunger and poverty. She shared why she never made it happen: “I just didn’t have the bandwidth.”

I think it was then that most of those in the room got it. No one — no one individual, no business, no nonprofit, no government agency — had the capacity to build a network like this themselves because they had to be singularly focused on their own organization’s capacity.

But it could be done by people banding together with a common purpose through this “band-with” network.

In the wake of this successful meeting, synchronicities abounded, and we could feel the forward momentum. For example, a small farm conference was coming up, and our early adopter farmer created a special workshop for more than a hundred people at the conference. He led various breakout groups, encouraging people to share their vision and needs.

And so it was that we launched the Northern Nevada Local Food System Network.

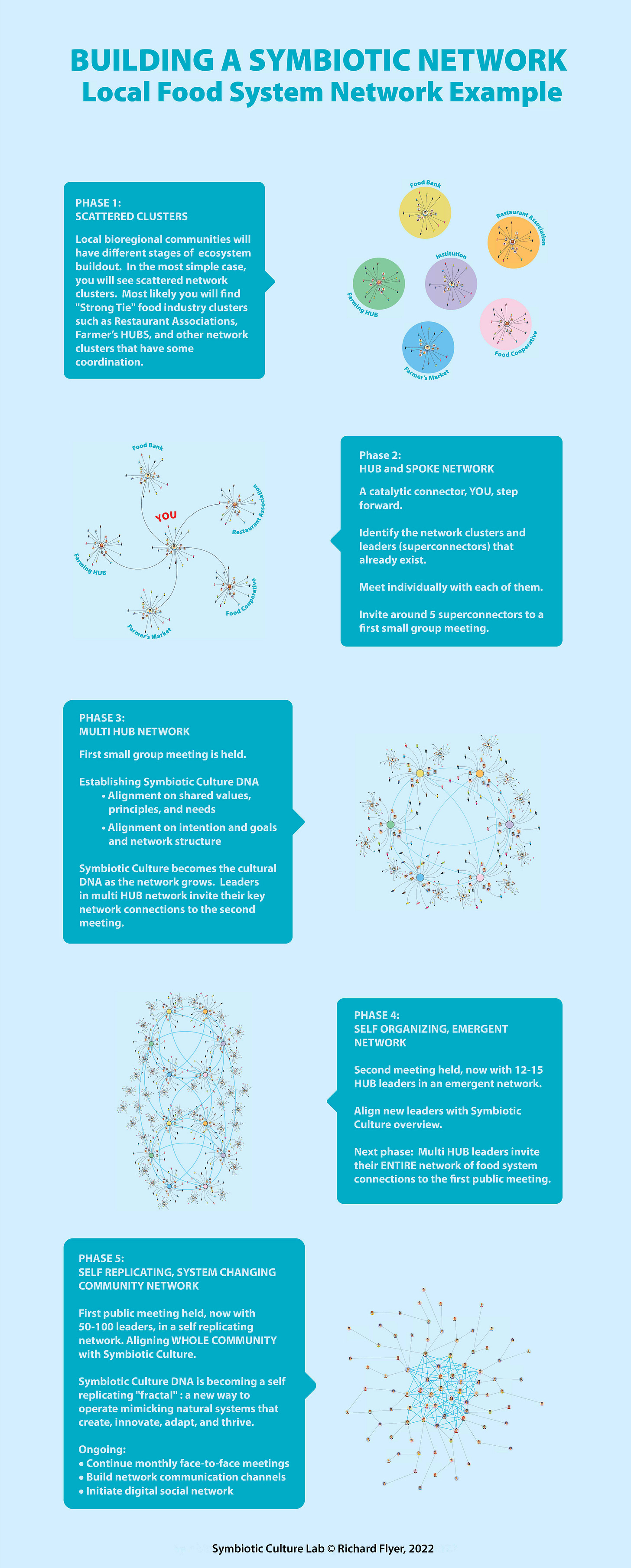

It began with one person—me—meeting one-to-one with individuals, sharing a positive vision and the literal mutual sharing of positive Virtues and energy. Once mutual alignment of intention, resonance, and coherence emerged through one-to-one sharing, it became natural to invite half a dozen super-connectors to meet in a small group, creating our initial leadership hub.

These leaders then invited their “downline” connections to a slightly larger follow-up meeting with a group of fifteen to a founding meeting and, finally, an all-hands-on-deck public breakfast meeting that expanded our leadership network tenfold and nature — in this case, the other aspect of human nature, the innate desire to collaborate and cooperate — took its course.

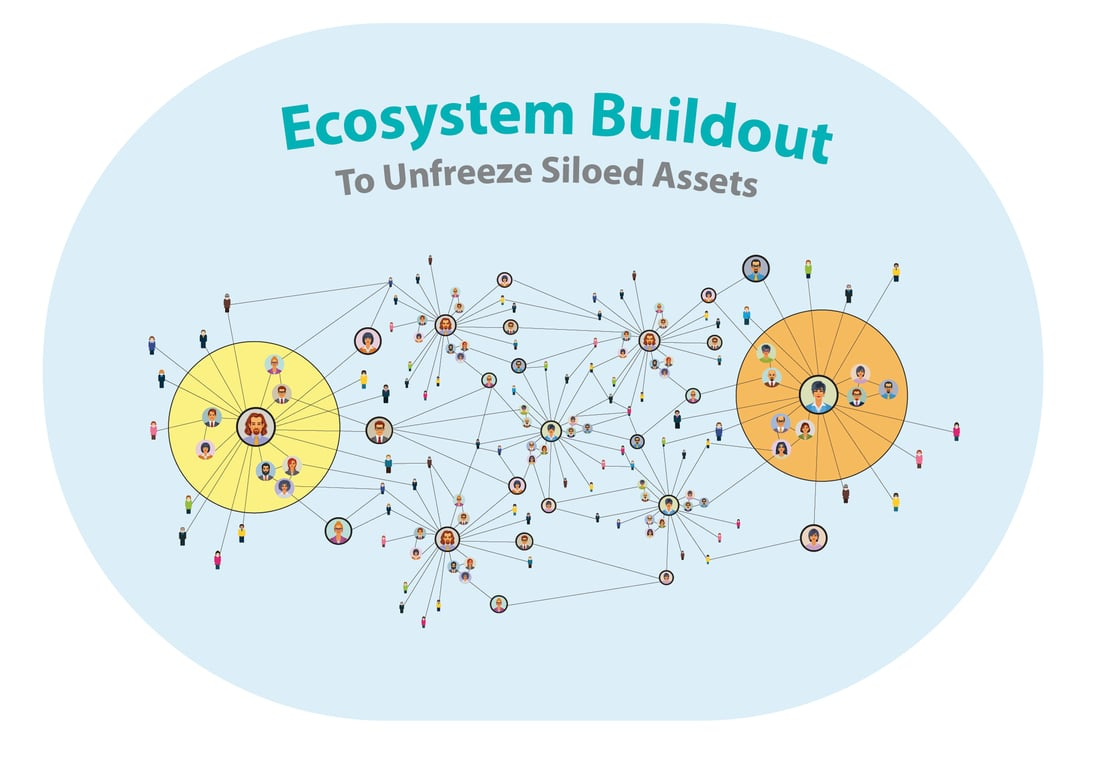

You’ll notice in the graphic below we talk about “Symbiotic Culture DNA.”

We will develop this idea further in Chapter 8, but for now, it means that by following the process outlined in the graphic, coming from an underlying, “encoded” pattern in the Ancient Blueprint, we create a repeatable pattern that can work in any community anywhere. We used it to build our Local Food Network, but as you will see in Chapters 9 and 10, it can be used to address other community needs – like getting to know your neighbor or supporting environmental awareness and the arts.

Through the power of “third-party trusted connections,” where individuals bring other people and networks they know and trust to the “party,” we became a “self-replicating, system-changing, catalytic community network” for new connections and collaborations that emerged naturally, generating significant value for each stakeholder, the network, and the whole community.

“Shortening the Path” – Our Social Media BEFORE Social Media

One of the concepts that emerged we called “shorten the path.” For example, a great benefit of the tech revolution and the emergence of the Internet over the past twenty-five years has been that communications happen more quickly, and more can be accomplished in a shorter period. At our regular public meetings, we initiated something we called “speed networking.”

We would intentionally instruct participants to “go meet someone you don’t know” and spend one minute talking about what they’re doing and their needs—one minute for them and one minute for their partner—no extraneous conversation. Then, we would have everyone introduce their partner to the larger group and vice versa.

This proved to be fun, energizing, and highly effective. Through this choreographed process, people experienced a symbiotic community. Bridges were built, and we were literally “wiring” the community.

Shortening the distance between network leaders led to other spontaneous connections that spawned interesting and unique projects. One incident that happened at the inaugural meeting comes to mind. This could be introduced as “a rabbi, an imam, and a networking catalyst walk into a bar ….”

The rabbi and imam were sitting together and, in conversation, discovered they were both looking for halal food sources suitable for the dietary laws of Muslims and Jews. The two of them ended up creating a co-op for halal foods.

In another case, what I have come to call the “story of the Pastor and the Pagan” I intentionally matched up an unlikely pair — one was an elder who identified as “neo-pagan” who taught classes on regenerative farming at a local regenerative school. He would never on his own have anything to do with Evangelical Christians, whom he had pigeonholed as prejudiced and anti-gay. The other was the evangelical Christian pastor of a church, who had a huge permaculture garden in the backyard of his church.

I intentionally sat them together at one of our breakfast meetings, a perfect example of “trusted, third-party connections” and Symbiotic Kinship. I was the trusted third party who knew them both, and even though I didn’t formally introduce the two, the trust in the symbiotic culture we had created got them talking, sharing their common desires and passions around food, and building our local food system.

Using trusted third-party connections to bring together individuals and communities that otherwise might not have connected seemed to reflect and amplify Stanford sociologist Mark Granovetter's 1973 paper “The Strength of Weak Ties.”

Granovetter asserted that while “strong ties” (close friends, family, and immediate community, people who are “more like us”) are fundamental in reinforcing identity and emotional well-being, it’s the “weak ties” (casual or more distant relationships, people “less like us”) that provide our new opportunities in life.

On a personal level, this can mean a new job or a romantic partner. On the community network level, it means linking otherwise unrelated organizational “clusters” so that more “good” can flow through a community. When we build a bridge between separate and siloed networks, we liberate the “frozen assets” of both communities.

In the examples above, each otherwise polarized community—Jewish and Muslim, Evangelical and atheist—had access to new people and a broader view. This may even have led to unlikely friendships that reinforced what we have in common above and beyond our “tribal” identities. That was a “collateral benefit” of our networks—expanding individuals beyond “communities of comfort.”

Not only did we “shorten the path,” but we also created new paths where none had existed.

The graphic below shows how a trusted third party makes a bridging connection through their weak tie connections.

This is the perfect example of how to bring people together across silos in Symbiotic Kinship.

We created a new connection frame—network scaffolding—around local food, NOT a conversation about different political and religious beliefs, cultural identities, or movements.

While creating conversations for mutual understanding and de-polarization is certainly beneficial, those types of conversations became unnecessary in our group. Our conversations about “what we want to create together” took precedence – and broke the trance of separation.

Because we weren’t there to air our religious or political beliefs that might have been in conflict, we bypassed the typical “judgment filters” in our “reptilian brain” that would evoke fear or wanting to fight the “other.” We were already building heart-to-heart bridges by working together.

This didn’t just happen; there is a method to the “magic,” and I will teach you how to do this in Section III – and that has to do with a concept I introduced earlier – “space-holding.” Even though I probably wouldn’t have used this language then, we were creating a “sacred space,” like a temple or cathedral. Upon entering, it is appropriate to remove one’s “street shoes.” In this case, it’s the beliefs, judgments, and narrow identities we hold, our prejudices, and even our traumas.

When we create a setting that connects people who wouldn’t otherwise connect in everyday life, we allow them to find common ground, purpose, and action. In the case of the Evangelical and the “Neo-pagan,” the two men had the commonality of being elder organic farmers ready to share what they had learned with the community.

The magic of connecting around a compelling common purpose is enough — sometimes for a moment, sometimes forever — to lift people off the ideological battlefield and onto a cooperative playing field.

At a time when Facebook was still in diapers, our monthly face-to-face local food system network meetings were the “social media” that sparked connections, projects, regional cooperation, and prosperity. The small farm conference I mentioned earlier, where our farmer friend presented, brought this process to farmers statewide, and more stakeholders wanted to participate.

With new energy and growing participation, conversations emerged about structure and growth. One woman in the group kept pushing an agenda for us to become a nonprofit corporation. I patiently explained that I felt it best for the network to grow organically over a period before any decisions like that were made.

Besides, I reminded her that the network didn’t need to raise money or hire employees—its strength was in being a network-centric structure, a growth hierarchical project built and run by the stakeholders themselves.

It turns out she was unemployed from a previous job and had a vested financial interest in promoting the idea that the food system network become a non-profit, formal organization that could use her as its first director. These are the kinds of real-world conflicts of interest that come up.

That’s why the Virtues are key to success — or else we end up back in the old world of self-interest, only “What’s in it for me?” rather than “What’s in it for all of us?”

Creating “sacred space” through the practices of Virtues emanating from the Ancient Blueprint is the foundation – and there is another key step in extending these virtues throughout an entire community …and beyond.

It reflects a principle we introduced in Chapter 6, Subsidiarity – meaning “Charity Begins at Home,” start where you are and radiate outward from there. This is particularly true as we recognize that global change can only happen locally but simultaneously as part of the awakening of thousands of communities.

Returning to the origins of our first network, the buy local network, remember it began with a group formed in response to a worldwide crisis – the impending invasion of Iraq. Yes, we could have gathered our group and marched for or against something happening halfway around the world. Instead, we focused “at home” – how do we face the conflict and polarization in our own community? Or, as some wise individual once quipped, “How can we have peace in the Middle East when we don’t have it in the Middle West?”

So we began with the people we knew—our own trusted connections—and had these people invite their trusted colleagues, and so on. We recreated that same pattern for our Food Network. I began with individual phone conversations and one-on-one meetings. From there, we went to a small group of people who had already bought in and then on to their connections until we had literally hundreds of businesses and thousands of people in a radiating circle of trust.

It turns out we weren’t reinventing the wheel here. We weren’t making it up as we went along.

We were following in Sarvodaya’s footsteps to create what we call “fractal community empowerment.” In plain English, that means we create a functional process and system that can naturally recreate, reproduce, and spread itself, over and over, in community after community.

As we will see as we explore the other networks that we developed in Reno, these emanated from an “organized and unified” community ground of being that extended the Ancient Blueprint first one-on-one, then to small circles of trust, then to a larger group of like-minded collaborators, and finally to a larger distributed network.

Every phase recreated the fractal of loving virtues.

That’s how we reached and impacted all of Northern Nevada, how Sarvodaya created its network of village economies, and how anyone reading this book and motivated to do so can become the seed wherever they are.

In Chapter 8, we will discuss fractal community empowerment, a five-step process for embedding and proliferating Symbiotic Culture DNA.

Local, Cultural Change Strategy – Why Paradise DID NOT Get Paved

Our Northern Nevada Local Food System Network also led to a profound shift in local culture that impacted economics and politics as well. At the time we launched—late 2005, early 2006—there was a general feeling that small farming was a thing of the past.

Local civic and business leaders were being enrolled in the idea that all this farmland should be sold and that the local economy would benefit more from development — condos, apartments, single-family dwellings, malls, and parking lots! Potential tax revenues put dollar signs in their eyes.

However, a funny thing happened on the way to paving over paradise and

putting up the proverbial parking lot.

Within six months of starting our network, there was a dramatic cultural — and ultimately, policy — shift in Northern Nevada. Small farming, farmer’s markets, and a vibrant local food system became the new culture.

Culture does indeed drive economics and politics, and so our small network impacted the community at large. Consider what sparked the original Buy Local network in 2003: the war and an undercurrent of concern about big box and chain stores “colonizing” the local economy and extracting wealth rather than circulating it locally.

As you will recall, there were those who wanted to “fight” Walmart’s incursion through economic boycotts and political action. Those of us who wanted to use that energy to build a vibrant buy-local network prevailed, and the success of the Conscious Community Network led to the Northern Nevada Local Food System Network, which became an innovative “nervous system” for the whole area.

We never had to petition the government to prevent them from developing farmland. There was enough consensus and public will to make that kind of political action unnecessary—still, the political and business community actually followed the people's will.

If you’ll recall, I’ve said throughout this book that global problems can only be solved locally. The global oligarchic system is well-entrenched, well-funded, and too big to take on directly. But we have shown that we can have a major impact on our own communities.

Also, fundamental change happens beneath the surface, under the radar, as new healthy relationships develop, like the mycelial networks we discussed in Part I. By simply changing the local culture around food, we created a political fait accompli without a partisan political movement or infrastructure.

This new symbiotic culture of collaboration created a new playing field that impacted the local community in many unexpected ways.

Remember the community garden project we didn’t start?

As a result of our Network, our networking, and the culture of collaboration we were building and supporting, many such collaborative projects emerged. Our focus, discipline, and strategic approach allowed projects like this to spin off and grow rapidly. We accelerated connections, conversations, and collaborations by shortening the path between our stakeholders.

We released hidden assets in the community that had been “frozen” in the more rigid, siloed business system as usual. For example, when we started out in 2005 – 2006, there was one community-supported agriculture project that connected residents directly with farming and subscription farmers. Within ten years, fifteen of these emerged. What began as three farmers directly marketing to urban residents, in ten years’ time, became 150 food-related businesses supplying restaurants and grocery stores.

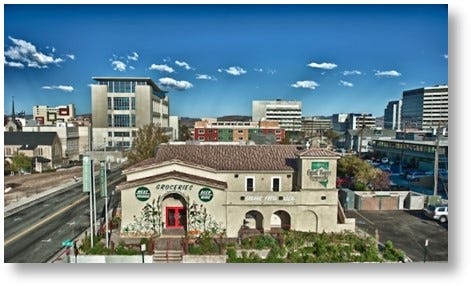

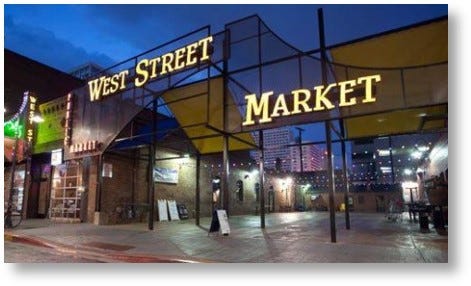

As more farm-to-consumer enterprises emerged, the City of Reno invested public money to create the area’s first permanent farmer’s market. That building became a public meeting place for activities around food, including multiple restaurants. More local folks gained access to healthy, organic food. To address this demand, the Great Basin Food Cooperative was started and grew into one of America's most successful food co-ops.

To be clear, the local food network didn’t own or promote the food co-op as some official spinoff project. The community-wide, expanded consciousness around locally grown healthy food supported the food co-op’s accelerated emergence “organically.”

Once again, as we built this new highway to a thriving local food economy, that road built us. Collaboration — because it involves humans — is always challenging. How do we balance and reconcile the collective eco-system with the human “ego-system”? I certainly had some ego moments!

As almost all of us were raised in a “taker” culture, most people are naturally guarded about issues of territoriality and ownership. Add to this all our past experiences around trust and control, and being a connector or catalyzer does become more of a spiritual practice.

None of what we accomplished could have been done without building

a “sacred, trusted space.”

We were building not just a symbiotic network around local food but a new culture, committed to embodying the virtues of love, cooperation, collaboration, service, and mutual benefit — a spiritually based, network-centric, global civilization rooted in regional economies to replace the obsolete, top-down global Culture of Separation.

Find out how we continued to develop a Unifying Worldview, the “Glue,” to guide our continuing actions in the NEXT POST — Chapter 8, Part 1: What Will Unite Humanity? — Decoding Symbiotic Culture DNA

Introduction: From “Reality Crisis” To “Real” Opportunity… Cosmic Love and Collective Intelligence

PREVIOUS POST

TABLE OF CONTENTS

NEXT POST

Richard, what a remarkable and inspiring achievement. I hope it will motivate many others to follow your lead.