Jesus Sends me a Buddhist! Chapter 4, Part 2

Embodied Virtues and Launching the First Symbiotic Network

Welcome to the Birthing the Symbiotic Age Book!

NEW here? — please visit the TABLE OF CONTENTS FIRST and catch up!

You are in Chapter 4, Part 2, Embodying Virtues – the Interface Between Heaven and Earth and Launching the First Symbiotic Network

Chapter 4 posts: Jesus Sends Me a Buddhist

Embodying Virtues – the Interface Between Heaven and Earth and Launching the First Symbiotic Network

Are you trying to figure out where this is All Going? Read an overview of the Symbiotic Culture Strategy, which embodies the Transcendent through the nodes of intersection within local, grassroots-empowered community networks.

Voice-overs are now at the top of my posts for anyone who doesn’t have the time to sit and read! Also, find this chapter post and all previous posts as podcast episodes on

Spotify and Apple!

Previously from Chapter 4, Part 1

Sarvodaya’s seamless integration of spirituality and the group’s ability to build bioregional ecosystem networks — creating a new society amid the old — captured my full attention.

Even today, as we face multiple global crises, no other movement offers humanity such a clear path forward. Through their national network of 15,000 villages and towns, with more than 5,000 of which have developed “Sarvodaya Societies,” they have built a parallel organizational network scaffolding for a new society alongside the official local and national governments.

While there are obvious substantive differences between the Sri Lankan and Western contexts, I’ve worked to translate their principles into what I call Symbiotic Networks. This book will provide you with a step-by-step approach to starting your own local community weaving movement — anywhere in the world.

Chapter 4: Jesus Sends Me a Buddhist! Part 2

Embodied Virtues and Launching the First Symbiotic Network

Embodying Virtues – The Interface Between Heaven and Earth

So, how do we unite spiritual and community development as one process? And what is the framework to bring Heaven to Earth?

I started to recognize that the Ancient Blueprint for a New Creation, found within the core teaching of the Sermon on the Mount — Love God / Love Others — was not just a poetic statement but a fundamental description of the participatory and relational nature of Reality, like Einstein's famous equation E=MC2.

There is some irony that the Sarvodaya Movement stands as a profoundly successful expression of Jesus’ teachings — but inside an ancient, South Asian, primarily “underdeveloped” Buddhist nation!

As we connect with the Transcendent Ground of Being, Cosmic Love pours through us and takes form as positive Virtues, first embodied within each person, then spread organically into the world through community networks such as the 5,000 real-world Sarvodaya Societies’ bioregional ecosystem networks.

Sarvodaya’s success raised another question for me:

How can we, residing in advanced Western societies with diverse, pluralistic, largely Christian-based cultures, make the transition from seeing ourselves as isolated entities within our own silos (such as nonprofits, churches, businesses, and identity-based groups) entrenched in a Culture of Separation, to start seeing ourselves as part of a unified, interconnected reality — a Culture of Connection?

Turns out the answer is not through any new, sophisticated, philosophical, academic, political, religious, or some new business plan or social movement captured by a myriad of spiritual, social, or political action agendas within the Culture of Separation.

In Sarvodaya’s new parallel Culture of Connection, the secret sauce turns out to be more radical than revolutionary and starts with First Principles. Following the Ancient Blueprint, universal Virtues and their embodiment provide a concrete pathway to bring heaven to earth.

If you are wondering what I mean by “more radical than revolutionary,” let me clarify. Revolutionary means a reactive, revolving system where one dominant group of elites is replaced by another—in other words, it keeps us on the same battlefield that caused the condition in the first place.

In contrast, “radical” means getting to the root — in this case, healing separation itself — bringing the Cosmos together in Love. So rather than waiting for change to come from “out there,” everyone in the community is called on to heal the separation “in here” — inside each one of us.

As mentioned before, St. Maximus the Confessor spoke of a virtuous circle. By practicing individual virtues such as compassion, patience, or charity, we can experience Cosmic Love, and by experiencing Cosmic Love, we are given the capacity to practice individual virtues!

This individual practice doesn’t happen in isolation but in a community of practice in the context of real-world action. And we don’t have to wait for the world to change first!

So, in Sarvodaya, each person commits to growing spiritually, what the Buddhists call “awakening.” Let’s be crystal clear — awakening here is radically distinct from the Western individualized, deconstructed, or decoupled version of Buddhist meditation that may be added to other practices like yoga, crystals, or chanting in some spiritual buffet of postmodern spirituality.

It’s awakening the individual personality by practicing the four virtues of Loving Kindness, Compassion, Joy in Other’s Joy, and Equanimity in the context of ever-expanding community spheres — starting with the person, then the family unit, then embodying the virtues in their organizations and the whole village or town, then as part of their local “micro-bioregion” (local region), including other life forms.

This, in turn, becomes part of the network of 5,000 Sarvodaya societies in Sri Lanka and, finally, a global network of virtue-awakened towns and cities. In addition to the four key virtues mentioned above, Sarvodaya inculcates other virtues/principles of social behavior, including Generosity, Pleasant Speech, Constructive Work, and Social Equality.

To reiterate a previous point, the virtues and principles of what we call the culture of connection will turn our upside-down world right side up! The power of Virtues lies dormant within each of us, awaiting our application and practice. They are accessible to everyone and require no advanced degree or intellectual brilliance, nor do they require spiritual enlightenment.

Remember what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said:

“Everybody can serve. You don't have to have a college degree to serve .... You only need a heart full of grace, a soul generated by love.”

This is where the rubber meets the road, the test of true religion and spirituality—this power must be anchored in Reality through how we live, and Sarvodaya has been demonstrating this for more than sixty-five years.

As individuals and organizations in Sarvodaya release the power and energies of the Virtues into the newly created network nodes of intersection, between silos, it spreads throughout the whole region through this consciously created infrastructure, uplifting everyone. Nodes here are the leaders of organizational silos. This could be one of the world’s best and largest examples of what is called Nexus Agency.

That is, this agency, the power to impact one’s own world, can be activated not just in one person or within one organization but from an ever-growing, bottom-up network of multiple coalescing networks dedicated to serving the common good of all. This is why the Sarvodaya Movement got my full attention.

To me, this approach holds the key to the next step in human social and cultural evolution itself — from single-issue / silo approaches to multi-issue, multi-siloed networks.

It is a “multi-scalar” network transformation from a me consciousness to a we consciousness — an approach that we sorely need today. Dr. Ari has proven that cultural change can be reproducible, “scaled out” in each community, and then “scaled up” within one nation.

And then … why not within other nations? Why not all around the world? Dr. Ari was already inspired and informed by this global vision, much like the vision that Jesus showed me:

Dr. Ari said, “We dream of a world that is a commonwealth of self-governing communities. We dream of people enjoying participatory democracy, where all human rights are respected, where spiritual and moral values are strong, and where people respect nature.”

Dr. Ari’s Sarvodaya Movement, and later the symbiotic networks we created in San Diego and Reno, transformed the local culture. First, they embody the Virtues, giving us the capacity to unify our local community. Second, they extend this “virtuous field” as an actual power to build local symbiotic culture and networks.

These networks are fractals of the Ancient Blueprint, and as you will read in Section 2, they take the form of multi-nodal distributed circles of trust. And we emphasize once again that these networks are self-governing — they emerge from individual awareness and agency, not a top-down imposition. Participation is by choice, not from social, religious, or political pressure.

So, in answer to my prayers, Jesus did indeed send me a Buddhist.

But the synchronicity didn’t end there. At the end of the enlightening article that introduced me to Sarvodaya in the New Options newsletter, I was surprised to find a letter from a local professor at San Diego State University! Naturally, I contacted him and found out he was conducting a program right where I was, in the Logan Heights community.

Now, not only did I have Dr. Ari as a guidepost, but I also had a new ally who, like me, was eager to see how the practices cultivated in impoverished villages half a world away could be applied in another poverty-stricken neighborhood in San Diego.

Launching the First Symbiotic Network

I asked myself, “How is it possible to consciously weave networks to bring everyone together with a common vision based on Cosmic Love, inspired by the Ancient Blueprint outlined by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount and fully expressed in modern times through Dr. Ari with Sarvodaya?”

Usually, it takes a natural disaster (or catalytic crisis) to wake us out of our sleepwalking and propel us beyond the “trance of separation,” expanding our ego boundaries and enabling us to work together. In some cases, it takes a senseless act of violence like 9-11, a mass shooting, or a public safety crisis!

The year was 1992. In a low-income section of San Diego called Logan Heights, it took continued gang and drug violence, really a public safety crisis, to create the conditions for people to want to work together in a new way.

This crisis gave me an opportunity to explore how conscious community weaving of symbiotic networks could be a driving force in efforts to deal with the dramatic real-life challenges of an urban environment.

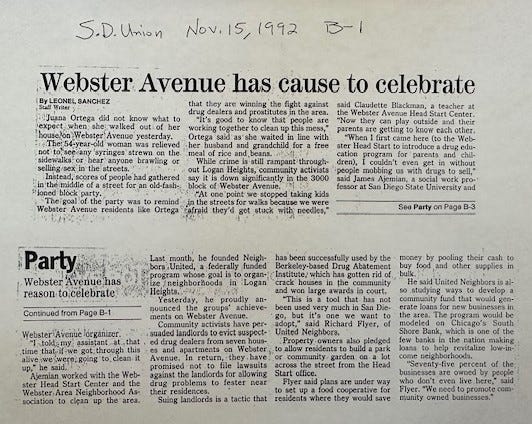

As a result of a community participatory process, I helped found Vecinos Unidos (Neighbors United) in the high-poverty and high-crime area of Logan Heights. Once again, a local crisis brought together this diverse African American and Hispanic community of more than 50,000 people—and the issue was public safety.

Like Sherman Heights, my previous neighborhood, Logan Heights, was beset with crime, poverty, drugs and the drug culture, apathy and hopelessness, and absentee landlords who neglected their properties. It was a neighborhood in trauma.

For most families, homes were like garrisons. Children didn’t play on the street. Women stayed indoors. Many men would hang out in groups on the street, drinking beer, without work or hope.

On one residential street corner alone, there were more than forty drug dealers selling cocaine and marijuana day in and day out. Many of the buyers came from the wealthier San Diego communities like La Jolla. For the most part, the police would drive by and do nothing.

Why? For one thing, there was no foundation of political or economic power in the community — basically, no one on the outside cared. Here was an area where absentee landlords owned 90 percent of the homes, and 90 percent of the businesses were also absentee-owned. Many of the homes had leaky roofs, and mold was a common problem associated with sickness in small children. Gunshots and murders were common.

Because most business owners lived outside the community, other than keeping their businesses safe, they had no investment in the quality of life there. The churches in the community had what you might call absentee parishioners — they grew up thirty years before in the area and now had achieved the American Dream and moved to the suburbs.

Ironically, it was these very churches that had supported their members’ economic advancement through mutual aid societies, making sure no one fell through the cracks and students had what they needed to advance. Although these upwardly mobile parishioners came to church on Sunday, they turned their eyes away from the poverty that remained in the area where they used to live.

So, here you had a disconnected web of scattered, siloed networks of individuals, families, Black and Hispanic nonprofit organizations and churches, businesses, city and county government agencies, and others that only focused on their own narrow agendas. At the same time, the fundamental quality of life in the neighborhood went unaddressed.

I would find out later that the neighborhood disconnection and siloing of organizations was a microcosm of society, a global Culture of Separation, whether you looked at this specific low-income neighborhood or mainstream middle-class communities and whole cities.

As I began to see first-hand, disconnection was only a symptom of a deeper spiritual malady of modern life.

I came to recognize that in a Culture of Separation, separate, competing silos are accepted as a natural state of doing business. It almost seemed like a control mechanism to keep us divided into our respective tribes and silos — part of a time-honored tradition of divide and rule by our political leaders.

As a result, we engage life in these group bubbles rather than seeing humanity as a whole. As I saw this on-the-ground reality, I began to recognize that we can’t address society’s complex challenges from within organizational silos that focus on single issues or narrow groups.

Basically, we can’t fix a broken system using antiquated problem-solving because that’s the same thinking that created the problem in the first place! This is fundamentally why the system is incapable of transforming itself.

In Logan Heights (and, for that matter, everywhere else), each of the individuals and organizations was in a reactionary, survival mode, just taking care of their own narrow agendas and needs.

I was shocked but not surprised that the African American and Hispanic community organizations and religious leaders didn’t know each other, nor had they ever worked closely together. Our outreach was the first time they were brought together for a common purpose.

So, the problems in the neighborhood just festered until people emerged who were able to bring the community together around a larger, higher purpose and a higher agenda.

We were blessed to work with a courageous director of a Head Start center located in the midst of drug dealing and a professor from San Diego State University. We held our first meeting right on the street after someone was gunned down dead in the area.

Based on what I had learned in Sherman Heights and Sarvodaya’s principle of empowering even the most powerless people, we convened this meeting to bring concerned residents together to come up with active ways of dealing with the community’s breakdown and the deteriorating quality of life.

We began with simple steps.

First, we got the people affected together to share what they were feeling and then brainstorm what they were willing to do. Second, we began to re-weave the web of a broken community by reaching out to the various leaders of community organizations, churches, businesses, and government and getting their buy-in and participation in common community action.

We started with peace marches (a demonstration of positive peace), walking down the streets to bring people out of their homes and create a united sense of hope. This was a kind of “table fellowship” with people from all walks of life coming together for a community revival.

We cleaned up vacant lots. We engaged the San Diego Police Department to become involved with our struggle to be free from violence, and they established neighborhood policing that brought back the local beat cop, who knew the people living on those troubled blocks. We confronted absentee landlords by getting the City of San Diego’s building code officers to begin enforcing the rules and regulations that applied everywhere else in the wealthier communities.

Fundamental to our success was encouraging people who believed they were powerless to have a sense of agency. Within weeks of our first meeting, residents of Logan Heights could see the fruits of their actions.

Bottom-up, grassroots networks act as catalysts and can be more powerful than any formal organizational initiative, especially government.

Initiatives that come from outside the community or from above often hold an attitude—often unconsciously—that “we know better.” This attitude tends to create passivity, dependency, and ultimately resentment. Grassroots movements like the one we organized begin by acknowledging and tapping the potential strengths of the community. Just as Dr. Ari discovered in Sri Lanka, this builds confidence and self-reliance.

Here’s an example. There were eight drug houses, one of them reputed to be the marijuana sales capital for the whole county. A liquor store owner owned four of the houses surrounding his store. If tenants paid rent, he turned a blind eye to what was happening.

Through our efforts to network together with local families, churches, charities, businesses, and government, we were successful in closing these drug houses down within six months. In comparison, when the city government alone tried to close two houses, it took them two years.

Amid the chaos, I moved into one of the newly liberated drug homes. Soon, I started holding meetings there. I gathered some men from the street who had before been bystanders, along with some street preachers, pastors, priests, and other community members, to go on nightly marches to the drug dealer-infested street corner.

Each night, we occupied the street corner with a message of tough love. We told the drug dealers, many of whom came to our street corner representing a powerful Tijuana, Mexico drug cartel, that we loved them as God tells us to love others — with only love in our hearts.

And — while praying and reiterating our love — we told them in no uncertain terms that we did not love their behavior. In retrospect, it must have been bizarre for these tough, seasoned drug dealers to be confronted by this large, rag-tag group of locals and leaders determined to re-occupy their own neighborhood.

Writing this, I am reminded of the #Occupy protests against the “one percent” in the early teens, which ultimately faltered because it focused mainly on what it was against, with no coherent concept of what it was for. Ours was a true “Occupy Logan Heights” movement, where there was unity of purpose and a core connection to the Ancient Blueprint - starting right where we lived!

We didn’t realize it at the time, but we modeled ourselves on the symbiotic culture of the Sarvodaya Movement and would apply this model to the Reno networks you will read about in the next section.

When we “re-inhabit” our consciousness with Cosmic Love and the Virtues, we are

re-occupying the “worldly empires of man” with heavenly energies, and we become—individually and as a community—the new wineskins suitable for new wine.

The impact of these marches was inspirational. More people who had been sitting on the sidelines waiting for help from “out there” gained the courage to stand and march with us. That old saying, “There is strength in numbers,” is certainly true. The bolder our committed group became, the more neighbors showed up in numbers, the easier it was for others to join us.

This was like a “public proclamation” from residents that they were standing up to save and take back — really to occupy their own neighborhood.

And … we had to face some real dangers.

One day, I arrived home to see a guy selling drugs right in front of my house. Someone with an expensive car — clearly from outside the neighborhood — had come to buy drugs in front of MY home. I got out of my car and had a conversation with the buyer first. “How would you feel if I came to YOUR neighborhood in La Jolla to buy drugs in front of YOUR house?”

I didn’t realize it at the moment, but I was still angry about a disagreement with someone else I had earlier, and this added to my righteous indignation.

Next, I confronted the drug dealer. I told him to get off my property. Then, almost in slow motion, he took out a knife and lunged to stab me in the chest. As I moved away, I had a flash of insight that I was bringing my own anger into the situation and realized I could release it. I did, and I was no longer angry at the dealer — instead, I just saw the potential within him.

At the very moment I chose to let the anger go, it was as if a powerful light came from within and surrounded me, like the experiences I had in my dreams. In a split second, the knife, instead of ending up in my chest, was thrown down to the ground beside me. It was only in retrospect that I remembered Catalina’s words, “There is no need to fear evil.” The dealer looked at me as if he had a question, walked off, and left the neighborhood, never to be seen again. The buyer drove off in his car.

Moving Logan Heights into Self-Sufficiency

Our movement, which started as a response to drug dealing and gang violence, now broadened to focus on community and economic development. In the process, I realized there are two disempowering ways we commonly think about poverty.

On one hand, there are those who imagine that poverty is a personal issue, that poor people are apathetic, lazy, or even mentally deficient.

On the other hand, there are those who are seemingly more compassionate, saying these people are victims of “the system” and incapable of taking care of themselves and so must be subsidized with charity or public assistance.

Neither of these viewpoints cultivates self-reliance, self-sufficiency, or self-empowerment. Nor do they get down to the granular nitty-gritty that will solve the underlying problems and transform the community.

Within the Culture of Separation, it’s not only tolerable, but it’s an acceptable “externality” to have a whole community living like this for generations.

Fortunately, I had Sarvodaya’s radically practical approach to guide me. Instead of viewing those who populated the Logan Heights neighborhood as either villains or victims, I saw them as individuals with the power to change their lives and their neighborhoods.

The more I reflected on the external factors that reinforced passivity, apathy, and lack of self-respect, the more I realized that neighborhoods like Sherman Heights and Logan Heights were more like “third world” countries than American neighborhoods.

Again, this may sound a bit extreme, but let’s get real. In these poor communities, home ownership was rare. People paid rent to landlords living outside the neighborhood and bought their groceries and other items from stores also owned by outsiders.

Instead of money staying in the neighborhood, circulating, and prospering the local community and its residents, the money went to owners who used it to invest where they lived, outside, in their own communities. In this regard, Logan Heights was like a domestic “colony” in the context of dollars that were extracted into the larger, mainstream San Diego economy.

If you followed the money, you followed it out.

To give you an example of the outside-in / top-down approach by powerful and wealthy individuals and governments, Sol Price, founder of Price Club (now part of Costco), was able to benefit from the $10 million Gateway Marketplace project funded by the city and county of San Diego. He promised to provide local jobs and local business ownership.

The project did neither as businesses like Price Club moved in from the outside, bringing their own employees and their own partner businesses that were then able to take advantage of the Opportunity Zone tax breaks. They used government funds with the promise of solving the problem of poverty and ended up reproducing the old economic/extractive system.

Once again, I was reminded of Sarvodaya. Like the impoverished Sri Lankans, residents of Logan Heights had yet to learn the lessons that come from ownership. Our job became helping people help themselves by taking back their communities — to participate in their own spiritual, social, and economic development and total community revitalization.

Interestingly, we found this position was not popular with the entrenched “poverty organizations” dependent on government handouts. The fact that each of these well-intentioned nonprofits and charities competed with all the others for the crumbs of government funding was also an obstacle to getting them to cooperate.

In retrospect, two things become clear. First, silos are a feature of our Culture of Separation, not a bug. In other words, there seems to be something intentional built into the system that discourages cooperation. Silos are the perfect organizing system for divide and rule.

The second point is closely related to the first, that the neighborhood is but a microcosm of the global economy — the extractive relationship between the dominant San Diego economy over and above low-income communities seems to be the same relationship between the global economic system with its ever-growing oligarchy and the rest of us in every community on the planet.

Okay, back to the story!

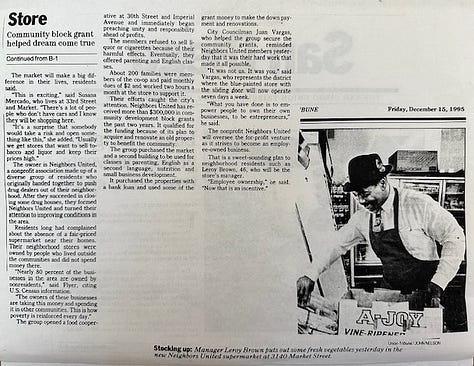

Fortunately, our success in cleaning up the neighborhood and bringing neighbors together for a common purpose led to support from many of these nonprofits, churches, and the city government. We started a food co-operative—using the same building that once housed a liquor store—which was at the time only the second low-income food co-op in the United States, the other being in Park Slope, Brooklyn.

Most of the families who participated — there were about 500 of them — were poor Blacks and Hispanics. For once, they were able to get fresh produce and groceries at a store that kept money INSIDE the neighborhood rather than extracting money out of it.

The local city councilman for the area took an interest, and he helped us get a community development grant of half a million dollars. With that, we were able to buy a new building a few blocks away that housed the community-owned food store and a community center in a rear building.

At our grand opening, all the local TV stations showed up. We had a local Hispanic parish priest and an African American minister do a blessing at the opening. This was certainly a local feel-good story — two clergy blessing the first community-owned food store in that neighborhood.

Lessons Learned

I learned many lessons and skills from my community work in San Diego. I learned that intentional symbiotic networking is a powerful way to bring people together to solve real-life situations, even violent and complex ones. We got people and organizations working together, sometimes for the first time, building long-lasting relationships after the crisis was over, as evidenced by our new community center and food co-op.

We created a new nonprofit, Vecinos Unidos (Neighbors United). We felt successful, and we were. We changed the community for the better, as crime decreased by 75 percent, but we didn’t transform San Diego. That is, the network didn’t expand to the whole San Diego region.

There were several reasons.

The primary one is as old as humanity. As Neighbors United grew to become a formal organization, it ended up having the same ego conflicts as other groups. I know this to be true since my own ego got in the way. I ended up having conflicts with the formal board of directors about future plans. Lacking spiritual maturity at the time, I probably contributed to the problem.

The second reason is that the group of people who organized Neighbors United was not aligned with the spiritual focus of working from the universal Virtues of Love and the Golden Rule.

That is, we shared no common spiritual understanding to make meaning and sense together. Like the “Tower of Babble” I referred to earlier, we had no way of including and transcending our different belief systems. Consequently, we deemphasized the spiritual foundation and formation—the secret sauce that has allowed Sarvodaya to thrive for more than sixty-five years.

We acquiesced to the popular notion of activism at that time — work on improving external conditions and the hope that spiritual understanding would emerge. That never happened. The more the group became focused on “external” projects, the more we lost spiritual coherence and our sense of purpose.

Something else I didn’t recognize at the time is that a project such as building a food cooperative or community education center can take a group’s entire bandwidth. The more time you spend on projects – worthy as they may be -- the less time you can devote to building network linkages in an ongoing, ever-expanding way.

This gets to what would become my single most important distinction in translating Sarvodaya into the West. Sarvodaya started with very economically poor villages (within a “developing nation” context), with hardly any infrastructure such as roads, irrigation, businesses, pre-schools, and banks. That’s how they galvanized popular participation—cooperating to build what was not there before.

In the “overdeveloped” West, we have an overabundance of infrastructure (cars, roads, TVs, computers, consumer choices) and an overabundance of businesses, organizations, interest groups, and other activities that compete in separate silos. As you will see later in Section 2, the key to bringing people together in the West is not building a new project like I described above but rather connecting the Good already happening in a local community — bringing together the existing forces of goodness and good works together in common action.

To do that would require a different mindset and heart-set, and I will share many examples of how we learned to do this in Reno, Nevada, in Section 2.

So, because of what we didn’t know at the time, Neighbors United ended up becoming just another silo organization dedicated to doing good work, yet limited by its own agenda, competing with other organizations for funds and recognition. What began as a grassroots networking model, reaching out to the wider community, became a constrained container once the initial crisis subsided.

During this period of “training,” my own calling crystallized.

I was to bring together the inner and outer, the individual and community, into what I now call “symbiotic culture.” In a society that has become more compartmentalized and tribalized than ever, I was to help weave inner spirituality with the outer community — and inspire other individuals and communities to find their way to do the same.

These early ten years were my apprenticeship as I did my best to take high ideals like Cosmic Love, unity, and community and bring them together in the day-to-day world of practical reality. I saw for myself what it looks like when a community transforms itself through caring action, mutual respect, and Shramadana — western style.

Summary

You could say that authentic religion and spirituality boil down to cultivating Love and Service—connecting the Transcendent with the Immanent—bringing Heaven to Earth in a real sense, uplifting humanity.

Symbiotic Culture – based on what I learned from Sarvodaya and what I applied in Sherman Heights (and later, as you will read, in Reno) -- provides a new framework for building a parallel society based on an Ancient Blueprint through commonly understood universal shared virtues in service of community needs. This culture and “radically inclusive” network can bring all civic groups, religious and spiritual organizations, and businesses in any micro-region dedicated to connecting and multiplying the good.

That’s the basic foundational “equation” of Sarvodaya Shramadana and Symbiotic Culture. It comes from a lineage of an Ancient Blueprint for a New Creation, the same one Jesus shared in his Sermon on the Mount: Love God / Love Others.

The master equation that we can freely download is truly embodied within ourselves and organically and naturally brings heaven to earth. It’s not just a beautiful, poetic description or metaphor — it’s an actual description of a relational and participatory Reality.

We are all part of this story of ongoing Creation — each of us has access to this power.

This is so radically different from the traditional, client-driven social service system, which is focused on the “outside” supposedly helping others who, as the saying goes, are “less fortunate.” I truly began to understand what Dr. Ari meant when he coined the phrase, “We build the road, and the road builds us.”

However, I needed one last learning experience, working within the system with more established community organizations, to truly see the contrast in approaches. It was the next part of my journey.

NEXT POST is Chapter 5, Part 1: From the “Charity Industrial Complex”

to Fractal Community Empowerment

Stay Tuned to find out what happened when I tried working within the system.

PREVIOUS POST

TABLE OF CONTENTS

NEXT POST