From the "Charity Industrial Complex" to Fractal Community Empowerment, Chapter 5, Part 1

Joining the Charity Industrial Complex and Fractal Community Empowerment

Welcome to the Birthing the Symbiotic Age Book!

NEW here? — please visit the TABLE OF CONTENTS FIRST and catch up!

You are in Chapter 5, Part 1, From the Charity Industrial Complex to Fractal Community Empowerment

Chapter 5 posts:

Joining the Charity Industrial Complex and Fractal Community Empowerment

From the Charity Industrial Complex to Thinking Outside the Silo

Global Oligarchy or Community Self-Governance? and Bringing Heaven to Earth

Are you trying to figure out where this is All Going? Read an overview of the Symbiotic Culture Strategy, which embodies the Transcendent through the nodes of intersection within local, grassroots-empowered community networks.

Voice-overs are now at the top of my posts for anyone who doesn’t have the time to sit and read! Also, find this chapter post and all previous posts as podcast episodes on

Spotify and Apple!

Previously from Chapter 4, Part 2

That’s the basic foundational “equation” of Sarvodaya Shramadana and Symbiotic Culture. It comes from a lineage of an Ancient Blueprint for a New Creation, the same one Jesus shared in his Sermon on the Mount: Love God / Love Others.

The master equation that we can freely download is truly embodied within ourselves and organically and naturally brings heaven to earth. It’s not just a beautiful, poetic description or metaphor — it’s an actual description of a relational and participatory Reality.

We are all part of this story of ongoing Creation — each of us has access to this power. This is so radically different from the traditional, client-driven social service system, which is focused on the “outside” supposedly helping others who, as the saying goes, are “less fortunate.” I truly began to understand what Dr. Ari meant when he coined the phrase,

“We build the road, and the road builds us.”

However, I needed one last learning experience, working within the system with more established community organizations, to truly see the contrast in approaches.

It was the next part of my journey.

Chapter 5: From the “Charity Industrial Complex”

to Fractal Community Empowerment Part 1

Joining the Charity Industrial Complex and Fractal Community Empowerment

Joining the Charity Industrial Complex

I emerged from my experiences organizing symbiotic networks at the neighborhood level with mixed feelings. On one hand, my work no doubt had an influence in helping those in poverty-stricken San Diego neighborhoods make tangible positive change in their communities, as people who once believed they were powerless now began to experience both individual and nexus agency.

At the same time, I was frustrated that the positive impact of my work in Logan Heights didn’t seem to be scalable and had minimal impact on the larger San Diego community and economy. My ambitious focus remained unwavering, however — to get to the root of poverty, income inequality, and hunger — and to do so, I recognized I needed a larger playing field.

The road I’d traveled to becoming an effective community network organizer had built my own skills, competence, and expertise — and challenged me to integrate the Transcendent experiences of the past twenty years.

Maybe I now needed to apply that experience and knowledge, working with a larger, better-funded county-wide organization, one hopefully open to an expanded vision of what it meant to help the “under-resourced” help themselves.

I still had one question at that time:

Was it possible to fundamentally transform the system from within,

starting with a county within the United States?

The opportunity to find out once and for all came in 1997 when I was recruited to become the Executive Director of the San Diego Food Bank. The Food Bank was a program run by a larger, well-established nonprofit called the Neighborhood House Association.

Established in 1914 as a settlement house that assisted immigrants transitioning into the San Diego community, this organization had by the late 1990s become one of the largest nonprofit social service agencies in San Diego County. For example, they had the main contract for the region’s Head Start program, which at that time had a $36 million budget. The Food Bank had its own Board of Directors, who did the hiring and firing. However, the Food Bank still had to answer to Neighborhood House, the parent organization.

The Food Bank was connected to Second Harvest, a corporate-driven national network that distributed food that couldn’t be sold—including boxes of food that were damaged or close to their expiration date. Through Second Harvest, the Food Bank developed relationships with major food producers and manufacturers like Kellogg’s. They also accepted and stored food donated through local food drives, such as the Holiday Food Drive and the Letter Carriers Food Drive, which happened every May, where postal workers picked up food on their route.

To be clear, the Food Bank didn’t directly generally distribute food — it was a “bank,” a place where donated food could be stored and then sold at a huge discount to local groups like churches, homeless organizations, and other nonprofits that distributed food to the needy.

When I worked there, there were literally hundreds of these groups that used their own financial resources to buy food and then re-distribute them to their community. Selling donated food to nonprofit distributors at 14¢ a pound was the financial model that made the Food Bank partly self-sustaining. Most of the food donated was canned, boxed, or otherwise processed like the foods generally sold in mainstream supermarkets. At some point, we did find sources for fresh produce as well, but the system was understandably focused on less perishable items.

At a time when military bases were being converted for civilian use, the Food Bank was given a space in the former Naval Training Center in Liberty Station, San Diego. There, we enjoyed a 100,000-square-foot warehouse, manicured lawns, and a clean, beautiful, impressive facility. I inherited a worthy mission—to end hunger in San Diego County—along with twenty employees.

And so, at my very first meeting with my new staff, I asked the question, “How many of you believe we can end hunger in San Diego County?”

One hand went up.

Out of all the people who came to work at this organization every day, only one believed in and was truly committed to the organization’s mission. Houston, we have a problem!

This was my initiation into the nonprofit charity culture, where regardless of the organization’s purported mission, the one fundamental commitment was sustaining the organization itself — and for those working there, keeping their jobs.

The staff went about their work distributing food and ameliorating the problem of hunger in San Diego County, yet never really considered what it would take to eliminate the problem.

Never did they get to the root of why there was such privation in such a wealthy county, nor address how to help people help themselves out of poverty.

I looked at all the staff who didn’t raise their hands and asked, “Then, why are you here?” I told them I was committed to changing the charity culture from addressing the symptoms of hunger to ending the problem—living up to our stated mission. I told them, “Starting today, if you don’t believe that’s possible, I’m going to replace you.”

My statement probably shocked many of the people in the room because — as I found out later — nobody had ever been replaced once they were in place. This had gone on for decades, an ongoing entitlement, a forever position of “fighting hunger” because everyone knew hunger and poverty never end.

It's not that the Food Bank wasn’t having an impact. Of course, it did. And, of course, the people working there were good people.

We had a “brown box” program for seniors, where they received a box of food weekly and a WIC (women, infants, and children) program to ensure the most vulnerable got fed. We also had hundreds of community food distributors that relied on us as a source. However, I was looking to build on that to have a greater impact.

I started hiring people, mostly those with corporate experience and a track record for producing results. I expanded my staff to include new functions, like publicity. I hired a “number two” guy to handle operations and manage employees so I could focus on building this expanded vision and increasing fundraising capabilities.

In contrast to my “freelance” community networking endeavors, where I could be flexible and nimble, I now found myself part of the power structure—an already-existing system and dominance hierarchy with a stubborn resistance to novelty and change.

I was dealing with many longstanding and complex relationships that had little to do with distributing food, let alone ending hunger.

The bottom line — it seemed that the Neighborhood House Association liked things just as they were. The Food Bank was a feather in their cap that added to the perceived value and prestige of the parent organization. My perception was that those who ran the parent organization were not hungry for change but rather satisfied with the status quo.

The Food Bank board that I inherited was mostly from larger labor unions in San Diego and Imperial County. So, in addition to being an organization designed to empower the low-income community, there was the union influence as well—and with each stakeholder interested in preserving their job or influence, the mission to end poverty and hunger in San Diego became less of a priority.

Welcome to the reality of the Culture of Separation!

Still, I was determined to apply what I learned about building symbiotic networks from our neighborhood movement and upgrade the culture at the Food Bank. This worked to a certain extent. I noticed the staff becoming more enthusiastic, mission-driven, and even optimistic about the impact on hunger and poverty, above and beyond what the Food Bank was already doing.

For example, I recognized that the Food Bank was already a network, a hub for all the organizations distributing food in the county. There were a few hundred of these organizations, from church pantries to agencies, to help the homeless. And as I discovered working in Logan Heights, these organizations tended to operate inside their individual silos and rarely took the opportunity to collaborate.

I did see one opportunity for collaboration, however.

While these organizations got most of their food from the Food Bank, they supplemented their food buying at Costco and Price Club — better than buying at supermarkets, but again, not the ideal “best” deal. That’s when I got the idea of bringing these distribution organizations together to create a “buying club” where we could get much better prices than Costco or Price Club — and we would have more control over the quality of the food. It would also give these organizations a greater sense of empowerment and autonomy.

I met with leaders of some of these organizations to explore options to create a bulk-buying cooperative, a symbiotic network. Still, I didn’t stay with the organization long enough to make it happen (which I’ll explain shortly).

We found other ways to branch out, to have a greater impact on hunger and poverty in the county, and again help our constituency become more independent and self-reliant.

For example, we worked with a homeless women’s shelter in San Diego to help women develop independent business enterprises — what later would be called a “social enterprise.” We would get huge donations of dried beans, so we had homeless women at the shelter package them to sell them retail or through our network organizations.

We were also able to enroll other local networks in synergetic activities — networks that had never collaborated before. In addition to initiating collaborative networks, we performed the practical function of opening ongoing revenue streams other than donations and grants.

While I was looking to implement a more entrepreneurial social enterprise model, I could not ultimately overcome the “charity model,” where well-meaning, well-to-do folks got to feel they were making a difference without truly empowering the people they hoped to help.

This “hand-out without a hand-up” approach was part of the culture and lifestyle of the nonprofit class — what I’ve come to call the “charity industrial complex.”

As the head of the Food Bank, I got to play — and play successfully — on the charity/fundraising field. In fact, I am somewhat proud to say I raised almost $1 million gross for the Food Bank on one night in 1998. The event was called “A Taste of the NFL.” That year, I was able to make the Food Bank the beneficiary, and using Superbowl parties in the town where the Superbowl was being played, I was able to get tens of thousands of pounds of leftover food from these Superbowl parties donated and distributed.

The “Taste of the NFL” was truly a prestigious gig. Imagine a big hotel event with thirty-one famous local chefs and thirty-one NFL alumni players, each from the National Football League cities, headlining the party. In those days, tickets were hundreds of dollars per person. It was a celebrity-rich event, and the year I was involved, it featured Miss America and Evander Holyfield, a boxing champion in two weight divisions. Actor/comedian Drew Carey was the emcee.

For our silent auction, I was able to get TV/movie stars like Kate Mulgrew, who played Captain Kathryn Janeway on Star Trek: Voyager, to donate a script to be auctioned — as well as memorabilia from rock stars and musicians. This was when the final episode of Seinfeld was being filmed in nearby Burbank, and we were auctioning off a ticket to that event, including all expenses and an opportunity to be in the studio audience.

Sitting right next to me at the auction was the then-CEO of Coca-Cola (major sponsor of the event), who had a winning bid of $20,000. It was a heady evening indeed, hobnobbing with celebrities and raising a million bucks.

I could see how one could get used to this — living the high life while ostensibly feeding the poor. I could have signed on to enjoy this “ending poverty” lifestyle for decades.

Of course, I realize that the majority of leaders of charities are doing good and for the right reasons. However, here was my problem:

While nonprofits like the San Diego Food Bank and millions of other organizations worldwide are doing good and obviously helping people, the silo-based, single-issue approach can’t solve the underlying problems.

I would go even further here to contend that inside the Culture of Separation,

the problem isn’t meant to be solved.

Instead, it is by design — because on a perpetual battlefield, the problem is mitigated but never radically addressed at the root level. Think “War on Drugs,” “War on Cancer,” and “War on Terror” … these are endless wars!

I sadly concluded that the Culture of Separation has empowered an entire Charity Industrial Complex that depends on an unsolvable problem for its continued existence. Most of the people who work in this industry, and most of those who support the commendable charitable enterprises, may never stop to consider this.

So, with all good intentions, we continue to feed the problem (pun intended) and fail to see that each of the individual problems or causes is an “externality” of the Culture of Separation. To put it more bluntly, as the secular religion of materialism and global oligarchic forces have their way with the world, these problems are what’s left behind for the rest of us to deal with.

This type of “transactional” work dealing primarily with symptoms wasn’t aligned with my systems-changing transformational mission.

The Culture of Separation and the “Everything Industrial Complex”

Lest you think I am some deluded “conspiracy theorist” when I suggest this institutionalized dysfunction is “by design,” please recognize this is not conspiracy but reality.

This is not about a bunch of guys in a boardroom “plotting,” but the self-perpetuating system itself “plodding” along its own well-worn path of doing the same things over and over, where “progress” is defined as doing more of the same and hoping for different results.

How else can we explain how we spend $500 billion each year (trillions in the last decade alone) worldwide to support nearly ten million nonprofits, none of which has been able to stop civilization’s suicidal thrust?

Yes, I am saying, contrary to what the majority may believe, the answer IS NOT more money!

Also, I want to clarify I am not just singling out charities. That just happened to be my own vantage point of how the Culture of Separation operates, even when pursuing the best of intentions. Since my own experience some 25 years ago, I have come to recognize what I call the “Everything Industrial Complex” – an operating system that applies and institutionalizes the Culture of Separation in every aspect of our lives.

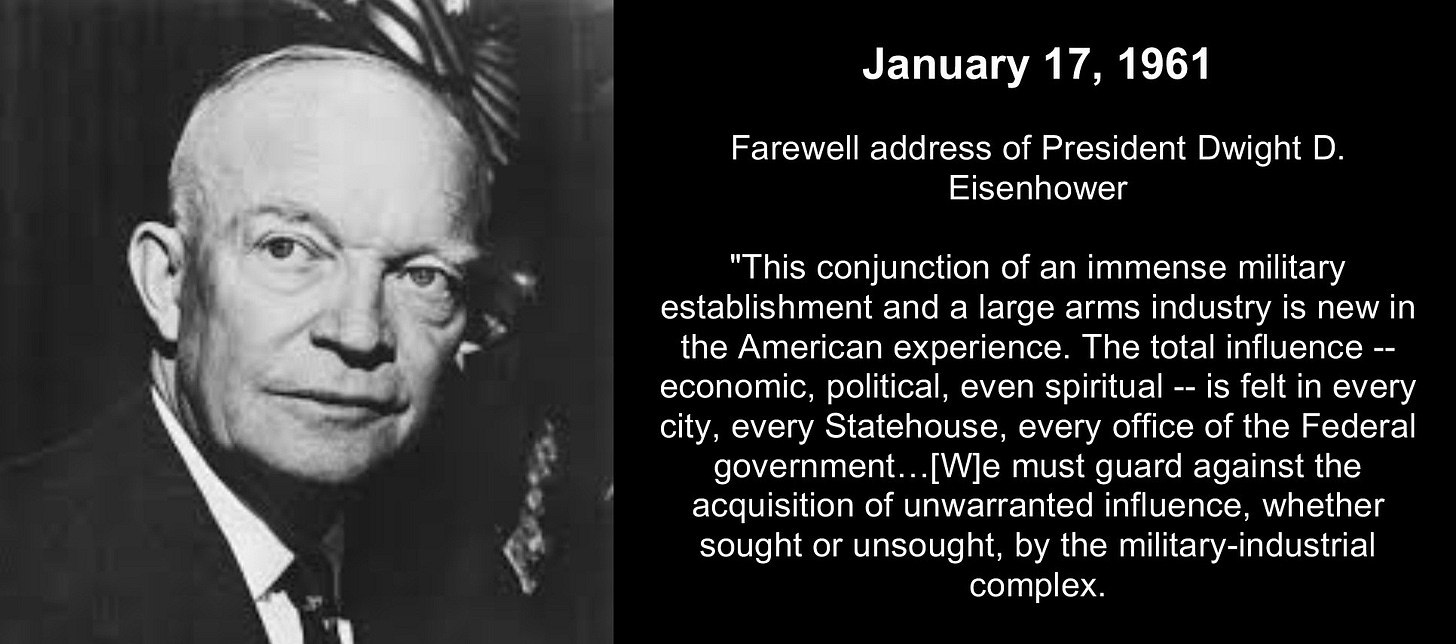

The idea of an “industrial complex” was popularized surprisingly by United States Army Five-Star General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Military Commander overseeing all the forces in Europe during World War II, who became the 34th President of the United States in 1953. In his eight years in office, he saw the establishment of a “government” above and beyond the elected government.

By the time Eisenhower left office in 1961, he was deeply concerned that this system had become a self-serving, self-perpetuating enterprise—an “industrial complex” designed to live forever, so to speak. Sound familiar?

The military-industrial complex Eisenhower warned of in his Farewell Address has tragically become the model for every other behemoth top-down system. More broadly, an “industrial complex” means a self-perpetuating system and system logic that always ends up pursuing their own interests, regardless of — or even at the expense of — the highest interests of people and society.

On a much, much smaller scale, I saw this at the San Diego Food Bank—every interested party involved had its own agenda, all of which pushed “ending hunger,” the organization's purported mission, to the back of the bus.

Just like the military-industrial complex has ended war…

What we now have “thanks” to the Culture of Separation is an Everything Industrial Complex—a model that perpetuates self-interest and siloed behavior at the expense of whatever industry or field is supposed to be doing.

As an obvious example, what about the Political Industrial Complex of a two-party dysfunctional American system of governance that spent $14.4 billion to elect a President in 2020, and where it is impossible for the two parties to cooperate on any beneficial legislation?

What about the Religious Industrial Complex, where religious organizations “compete” for market share, staying within their own silos rather than recognizing how the Ancient Blueprint could help all religious organizations collaborate for common community benefit – and transformation?

Think of any other top-down closed system that is highly funded and perpetuates “the way it is”: we have the Academic Industrial Complex, the Medical Industrial Complex, the Media Industrial Complex, the Scientific … Pharmaceutical …Entertainment … Education … and funding this entire Complex System is the Financial Industrial Complex, a banking system based on usury and financial speculation.

An industrial complex is part of the inevitable direction and trajectory of the Culture of Separation, which has perpetuated itself over the last several thousand years across societies, both East and West, to the point where they dominate nearly every aspect of society.

This is true because of a missing piece whose absence has become all the more glaring -- the systems themselves do not operate from Love and Service,

the fundamental values/virtues of all religious and wisdom traditions [to say nothing of countless exemplary examples of long enduring indigenous culture]

Without a connection to the Transcendent and the spiritual Virtues that flow from it, without an anchor in the Web of Love and the Web of Life, we end up with self-perpetuating dysfunction at best and tyranny at worst.

An antidote to Industrial Complexes — Fractal Community Empowerment

Our global economic system can absorb, commodify, disempower, and capture every approach that seeks to reform it. Even with the best intentions, as I began to see it, there seemed to be no way to break through the power and influence of the existing global system.

Further, all crises that we see globally—economic injustice, biodiversity loss, war, climate, hunger, poverty—are issues the Everything Industrial Complex “insists” are separate, discreet issues to be handled by its own “industrial complex.” They are not just interrelated but cannot be solved in isolation with a silo-based approach.

So, if you’ve already found this discussion to be a “stretch,” let me stretch you even further:

The only breakthrough solution worth anything is one that can solve every problem simultaneously at every scale, from person to neighborhood to community,

to planet, to nature itself.

Maybe the solutions to these wicked, entangled problems come not from one more “complex” but from something eminently “simple”?

I can’t help but contrast my experience with the high-roller crowd in San Diego with the simple mission and great success of Dr. Ari’s Sarvodaya movement in Sri Lanka.

Ironically, it is the simplest of endeavors – Sarvodaya – that has the capacity to solve these problems fractally – simultaneously at every scale by introducing and encouraging a new spiritual pattern in individuals and in each local community.

It all comes back to the Ancient Blueprint and applying that from “the ground up” as the root of all positive change.

In contrast to all of the self-serving “industrial complexes” that have complexified our modern world, Sarvodaya is focused on a simple “other serving” and “everyone serving” mission that encompasses not just economics but all aspects of life.

“Poverty must no longer be approached as a matter of mere economics,” Dr. Ari said in a Christian Science Monitor interview in 1981. “It’s a matter of human development. The real source of change lies in the people’s thinking.”

Dr. Ari recognized the need for human development as opposed to the siloed charity model that creates dependency and perpetuates hunger and poverty.

In other words, Sarvodaya is not a palliative model but a “fractal” community empowerment model, building the capacity and capability for political and economic self-governance at every level—from person to family, village to region, nation to world.

A fractal, shown by the GIF below, describes the repeated geometric patterns found within the physical world and within nature, but what about human society and its systems?

Fractal Community Empowerment, in contrast to linear or even exponential change, can happen simultaneously at all scales.

Instead of seeing our fellow humans as a marketable product, Dr. Ari envisioned them as co-creators of a parallel society, with its new Culture of Connection, embodying spiritual virtues and consciousness while building community network ecosystems —

starting with each person and each community.

Dr. Ari said, again in that 1981 interview, that we must “… measure success by the emergence of better human beings.”

In contrast to lavish fundraising events like the one we held in San Diego, Sarvodaya is about breaking through the caste, class, religious, and ethnic barriers, where people from all tribes work side-by-side so that all who participate grow internally as they produce external system-changing results.

“We human beings have lost out in the process of modernization,” Dr. Ari has said. “We have lost the relationship people once had between their external work and their internal development.”

Essentially, Sarvodaya has solved the tribe and silo problem — by connecting all segments of a community to experience universal kinship.

The insights I’ve just shared on silos, complexes, and the Culture of Separation, come from my experiences and realizations in the 25 years since I left the San Diego Food Bank. There is much more to share about the “fractal community empowerment” model.

In Chapter 6, on a Virtuous Economy, I will discuss how local communities can extend the Sarvodaya movement to build thriving Local Living Economies wherever they are.

Meanwhile, back to the story unfolding 25 years ago, I saw the fundamental discrepancy between my mission and the institutions that, for want of a better word, stood ready to coopt it.

Few, if any, of the colleagues and organizational leaders I met while heading up the Food Bank could grasp Dr. Ari’s underlying “human development” concept. No one was talking about practical ways of elevating people out of poverty, and no one ever challenged the unspoken rules of the modern economic system: that mankind is selfish, resources scarce, and the winner-takes-all mindset takes precedence over the wellbeing of “the least of us.”

Food was distributed to the needy, but nothing was done to address the fundamental structure of the extractor system. There was an acceptance of “things are the way that they are.”

So, there I was, standing between two cultures in stark contrast.

On one hand, there was the heady, glamorous world of professional do-gooding. On the other, there was a symbiotic structure that helped those with few resources collaborate to do good and do well. As for the buyers’ club, it was never implemented because, ultimately, my mission and the Food Bank’s mission were not a match.

They were content to go about caring for the collateral damage of the global economic system rather than addressing the problem at the cause level.

When the glory of that huge fundraising campaign wore off, I saw I was up against insurmountable odds — the formidable challenge of reforming the system from within — so I left.

Stay tuned for the NEXT POST is Chapter 5, Part 2: From the Charity Industrial Complex to Thinking Outside the Silo

PREVIOUS POST

TABLE OF CONTENTS

NEXT POST

So interesting and commendable. What can we do to action change so that the root of the problem, poverty, is addressed, rather than the symptom? Education. I think you have to be in it for the generations that follow. Sowing seeds now might begin to have some impact one or two or three generations or more generations down the line. Start with the kids, teach them to reject capitalism and look for alternative more sustainable ways to live.

We have reached many of the same conclusions about the "seed" of our culture, supported by industrial complexes is extractive and life-killing. I'd love to pick your brain and share insights of our work. Would you find a time we can connect? https://calendly.com/debilynm/30min

You can see my work here:

https://AmericanFuture.us

https://TerrifiedNation.com

Thank you for your clarity!