Building a Virtuous Economy: Symbiotic Kinship and Adam Smith - the Spiritual Wealth of Nations Chapter 6, Part 2

Welcome to the Birthing the Symbiotic Age Book!

NEW here? — please visit the TABLE OF CONTENTS FIRST and catch up!

You are in Chapter 6, Part 2, Building a Virtuous Economy: Symbiotic Kinship and Adam Smith - the Spiritual Wealth of Nations

Chapter 6 posts:

Regional Economies – a Virtuous Free Market…“Spiritual Capital” – The Key to a Virtuous Economy

Are you trying to figure out where this is All Going? Read an overview of the Symbiotic Culture Strategy, which embodies the Transcendent through the nodes of intersection within local, grassroots-empowered community networks.

Voice-overs are now at the top of my posts for anyone who doesn’t have the time to sit and read! Also, find this chapter post and all previous posts as podcast episodes on

Spotify and Apple!

Previously From Chapter 6, Part 1

The wisdom from the Ancient Blueprint, from Jesus to Gandhi, and today with Dr. Ari is the same — bringing heaven to earth means “Undergrowing” rather than overthrowing all “dominator” systems through a radical reformulation of the nature of power itself.

The Culture of Separation is characterized by force and bullying, by applying leverage and power (even amongst well-meaning social change efforts) over each other and other groups. Heaven comes to Earth as a Culture of Connection, another way — through the “all-conquering” power of self-giving Love.

There is a different way we can live — organizing our lives, community, and society.

Our Reno experience points us towards an updated and radically inclusive “occupy” movement, where we occupy ourselves with Transcendent Energies, really “re-inhabiting” ourselves with the highest Virtues and the greatest Good and spreading them locally through new network nodes of intersection.

Chapter 6, Part 2: Building a Virtuous Economy: Symbiotic Kinship and Adam Smith - the Spiritual Wealth of Nations

Symbiotic Kinship – The Foundation for a Culture of Connection and a Virtuous, Local Economy

Back to the story.

As we considered our criteria for what kinds of businesses should be included, there were those who insisted that this should be a network of only environmentally conscious, “green,” or sustainable businesses — what many today would call regenerative enterprises. True enough, for example, several of our early members and connectors favored organic agriculture over farming with chemical fertilizers, and at least one woman was fanatically insistent on that idea.

I took a different approach when I suggested the network be radically inclusive. Without realizing it at the time, I intuitively modeled Nature’s Web in designing this new “ecosystem” that I’ve come to call Symbiotic Kinship. In Nature, every organism is a factor in the web of life, so why wouldn’t we include “all of the species” of organizations in our new symbiotic enterprise ecosystem model?

Interestingly, John Mackey faced a similar dilemma when he launched Whole Foods, an enterprise that radically transformed the “natural food” market from a smattering of mom-and-pop “health food stores” to a multi-billion dollar marketplace. Mackey decided — wisely, in my view — to expand the store to sell non-organic items as well, wanting to make Whole Foods a “one-stop” shopping center that would directly compete with the established supermarkets. There turned out to be another benefit as well. The store attracted a broader customer base, who then tried — and preferred — organic.

My perspective prevailed when I made the point that this broader network would expand the customer base for the already existing “sustainable/regenerative” enterprises.

A strictly “regenerative” business network, on the other hand, would eventually reach its limits to influence the larger community, becoming just another regenerative network silo.

This view has been borne out in the nearly two decades since we launched it. For example, some local dry cleaners who were part of our network were using toxic chemicals at that time. However, increased consumer awareness led to more customers asking for nontoxic cleaning ingredients.

The marketplace had to respond out of necessity. So, it turns out, we didn’t have to have a “green” business network because this awareness was already naturally emerging in society.

Society was evolving, and so were consumer tastes and preferences. This radically inclusive, “market-based” approach, it turns out, is more aligned with our symbiotic network idea. While we can be “informed” by ideology, these siloed mental structures aren’t helpful when it comes to addressing real-life situations, collaboration, and effective problem-solving.

“Balkanization” around “tribal” identity will be a frequent theme in building the networks discussed in the coming chapters.

That’s because tribalism and the resulting silos of separation are endemic to how human beings operate, so we always need to be aware of this tendency.

I remember previous attempts in the Black and Hispanic communities in San Diego and other places to create Black-only or Hispanic-only business networks. I was even approached once to explore forming a nationwide, Christian-only business network. Even today, there are those in the movement for regenerative culture and community who believe that only those who think as they do should be included in networks to build their vision for a New Economy.

Many of these existing networks have the important purpose of building solidarity within these identity groups, but I have learned that they too easily become siloed and end up being absorbed or “captured” by the Culture of Separation. When you organize identity-based siloed networks such as these, they are incapable of breaking through the Culture of Separation—they really reinforce polarization and division without knowing or even caring.

Today, the same network siloing is happening in sustainability, “regenerative,” and other community movements. In conversations over the last two years, as I have been finishing the book, many of the leaders have told me that part of their strategy is to exclusively bring together like-minded projects and enterprises rather than reach out to mainstream organizations.

However, I believe that is a divisive approach because it unwittingly carries identity and political baggage, making it more about “social or eco-justice,” equity, being “anti-racist,”

and “anti or post-capitalist.”

While these positions may make sense inside of a siloed agenda, they are a hindrance to creating an independent movement seeking to unite siloes above and

beyond ideological divides.

This relates to another important hurdle we need to evolve beyond — the current fixation in society, especially business and media, about what has been labeled “inclusivity” — typically regarding race, gender, and today transgender — generally to overcome real and perceived past wrongs. And the excess of this line of thinking leads straight toward an extremely divisive identity politics that focuses on different groups’ rights.

Instead of a reactive rights-based approach, Symbiotic Culture focuses on duties and responsibilities to build a new society.

The Virtues that emanate from the Ancient Blueprint are a lot more about what we can give than what we can get. In contrast, the fixation on victimhood and entitlement puts people back into their familiar and limiting silos, seeking to align only with those who share similar beliefs or think the same way. This only feeds the Culture of Separation – now with new high-tech tools in its arsenal to amplify our division even more.

We don’t have to play that game, as it keeps us on the battlefield rather than on

a new playing field

The Culture of Separation seems to have turned the natural order of the Ancient Blueprint upside down. Instead of a culture based on identifying with the Highest Good, the Transcendent Order as our number one and our primary identity, separation focuses on man-made identities, especially the “Identity Politics” associated with Western cultures.

Of course, we will always have identities, that’s natural. But we don’t have to overidentify with those identities. Thanks to the inner regenerative, metanoia experiences of Cosmic Love I described in Section 1, I was able to see beyond the existing tribes and silos I had identified with before.

Yet—even with those transcendent experiences—I had to deal with my own limiting beliefs, from my “shadow self," that stood in the way of me being a community UNITER instead of a DIVIDER. This went far beyond “belief” or theory. I had to apply this in the real world, where diversity often becomes divisiveness, and people cling to their communities of comfort and beliefs out of habit.

I have already mentioned how I was previously anti-business without knowing it and how I had to overcome my limiting beliefs consciously and intentionally.

In the next several chapters, I will also discuss how I realized that, even with decades of deeply religious and spiritual awakening experiences, I was actually biased against organized, institutional Religion! I will share how I grew beyond my limiting view by intentionally participating in many religious and spiritual services I encountered. I even joined a men’s Bible study at an evangelical Christian church.

Getting back to the story, I followed my instinct to use these seemingly “economic” networks to build Symbiotic Kinship above and beyond silos and tribes.

Symbiotic kinship has to become foundational to our community outreach strategy—so we included all mainstream business owners, nonprofits, and governmental leaders beyond any human-made divide, just as Dr. Ari did within Sri Lankan villages on a national scale.

In addition to including all businesses from conventional to environmentally/regeneratively conscious, Symbiotic Kinship means you welcome leaders and their organizations who might not share your political or religious views or are in separate silos. You even invite leaders who you might not like personally. Your personal feelings or any ideology are irrelevant.

That’s why Symbiotic Kinship is not just a lofty ideal – it’s a PRACTICE and WAY OF LIFE.

Practicing Symbiotic Kinship means integrating the Virtues when building a community—in this case, a local living economy network—and the other Symbiotic Networks that we discuss in subsequent chapters. It takes inner character development and maturity to go beyond one's own likes and dislikes—that’s why the Virtues are a prerequisite to any efforts at wide-scale community collaboration, coordination, and systems change.

I’ve hinted at this in Section I, and I will have more to say about it throughout the book: In order to be a space-holder and effective convener of symbiotic networks, it’s essential to continue to deal with one’s own “shadow stuff” – past trauma and current prejudices, that can dehumanize “the other” and sabotage any well-meaning project. The Virtues support us in overcoming trauma and developing authentic healing and integration.

I’ve likened this space-holding to “taking off your shoes” when entering a sacred temple—leaving the separating identities from the battlefield of the Culture of Separation at the door while entering a new playing field, a new Culture of Connection focusing on shared Universal Virtues and weaving community networks around common, agreed-upon community needs.

The symbiotic network is not one more competing silo; it is the sacred space that can bridge and encompass all the silos, even those perceived to be in competition with one another.

It emerges from intentional, conscious kinship with all human beings,

not just those within our own siloed networks.

Consciously or subconsciously, that’s what we did in Reno. We kept our eyes on the prize and used Dr. Ari’s realization to focus on what people and communities have in common rather than what divides us.

Once we decided to go beyond green to include “all shades,” we faced another issue.

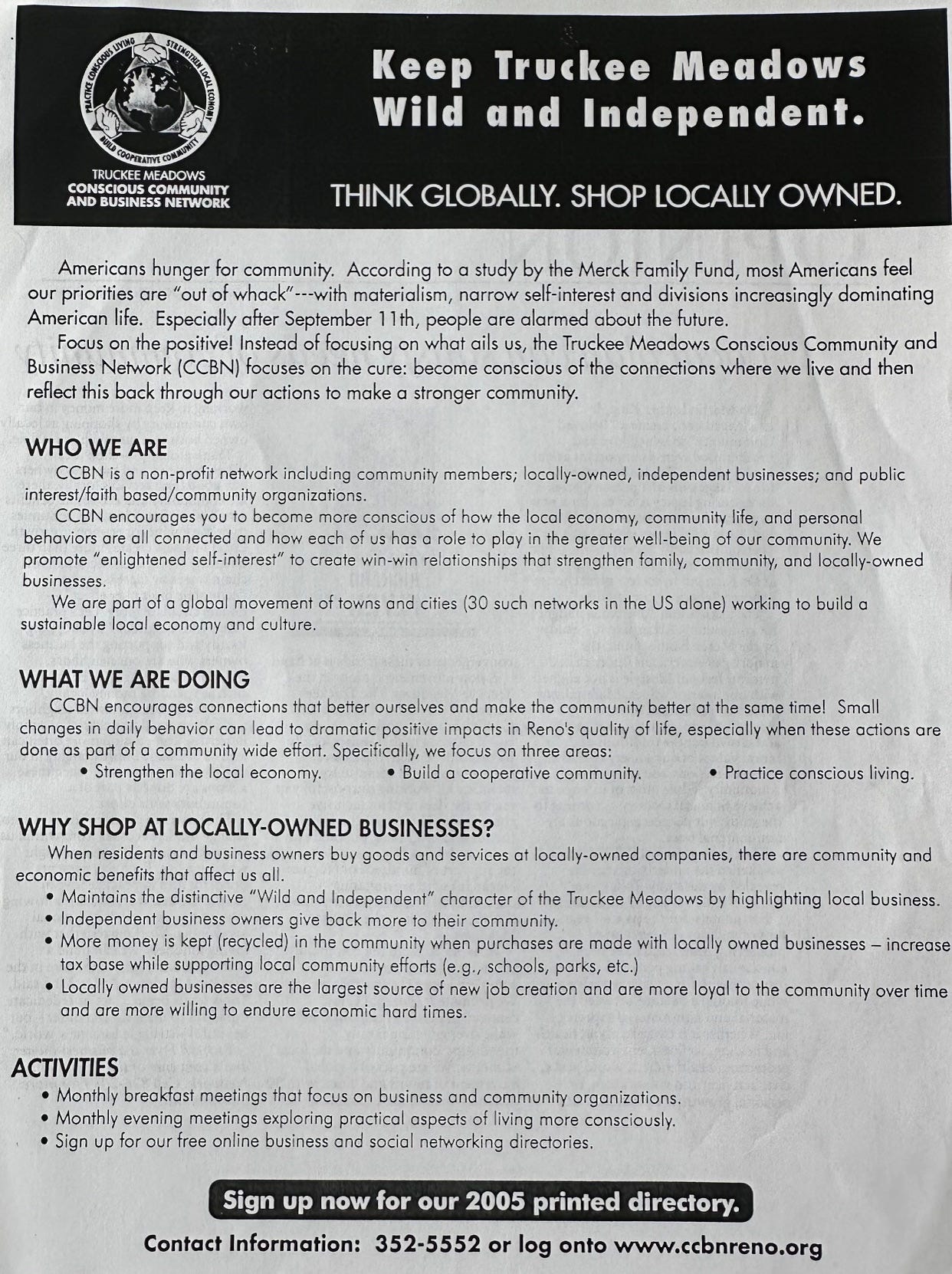

What businesses qualify as “local” businesses, and how do we include locally-owned franchises of larger companies? What about chain stores that wanted to be “good local citizens”? While we recognized the potentially negative impact big box stores could have on the quality of life in our community, we wasted no energy being “against” them.

Our intention was to build on the strengths that local businesses had in the marketplace: the number one customer desire was personal service with an owner that they knew over a period of time. Offering the best service to the customer turned out to be the number one differentiator. The other is the common “branding” of “shopping local,” which started to overcome the huge advertising “war chest” that chain stores have so that “local” could seep into the public consciousness.

After much discussion, we decided that to qualify as a local business, 51 percent or more of the ownership must be held by someone who lives in the region within a 50-mile radius.

Why was that important?

It had to do with each business being committed to sourcing its goods and services locally. “Locally” is up for interpretation. Consciously or not, we applied the Goldilocks principle – not too big, not too small, but just right. As you will read in Part III, we’ve come up with the term “micro-bioregional” to describe the area that is big enough to be diverse and small enough to be economically viable and manageable.

The sweet spot turns out to be much smaller than a bioregion ( a very large geographic region) but larger than an eco-village, intentional community, or neighborhood.

This would be on the scale of villages, towns, cities, and, in the U.S., the scale of

a County Government.

As I had recognized while at the Nevada Micro-Enterprise Initiative, it would have a huge positive impact on the community if large companies, local governments, and public institutions purchased goods and services locally in these micro-bioregions.

Large institutions and small companies need everything from paper clips to marketing. Companies with majority local ownership are more likely to “go local” to fill these needs.

Then there are franchises. I remember the case of a popular local coffee shop. Because they were a franchise, they had to source not just their coffee but other supplies nationally. And yet, they were a cherished “local business” that wanted to participate. That’s when we came up with the category “Affiliates,” businesses that couldn’t technically buy local yet supported the buy local campaign. That way, franchises could help raise awareness about the campaign, identify as supportive community members, and benefit from goodwill.

As we gained traction and momentum, everyone wanted to be a “local business.” I remember a conversation I had with a manager of a regional Walmart. “We’re a local business,” he said. “We employ local people.”

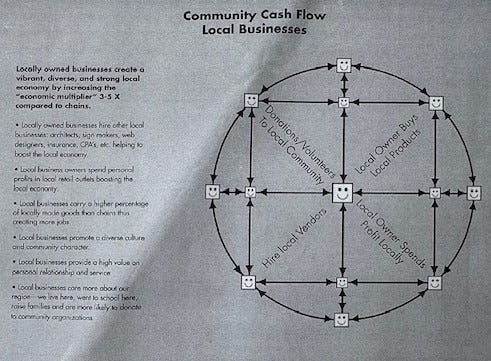

True enough, and … other than store employee salaries and paying local taxes, purchases come from and revenues flow to the Walmart headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas. As we came to see it, true locally-owned businesses did the most to “recycle” dollars back through the community; franchises were next because they could still share in the “buy local” consciousness.

An entirely different category was “vertically integrated” corporations like Walmart. Not only do they source their supplies from outside the community, but they also use in-house sources for training, design, publicity, and so on.

Ultimately, as publicly traded companies, they are beholden to their shareholders and not to any local community. In fact, that’s a significant challenge with large public companies — no allegiance to any place.

At the very bottom of the “buy local” list were the online vendors that barely existed at the time, like Amazon.

In addition to the “multiplier effect” that nourished our local economy through spending locally, the entire region was nourished by a project that grounded lofty ideals such as Love, Unity, and Service with practical actions — and created a sense of empowerment and agency.

We built community through monthly “breakfast meetings,” sometimes with up to 150 people, mostly owners of small, independent businesses, leaders of community organizations, religious leaders, government officials, activists, and residents. In total, about 500 businesses and community organizations took part.

The movement and the meetings were all about creating a new “collaborative culture,” a Culture of Connection, that modeled new cultural norms — practicing shared, Universal Virtues, being generous in making trusted, third-party connections, focusing on the economic well-being of the community at large, bringing polarized sides together in common purpose, and helping people recognize the value of service and collaboration.

It also initiated a new “hub-based,” network-centric leadership model that focused on informal “horizontal” personal connections rather than impersonal “vertical” dominance hierarchies. The best thing about it was that this culture was not “forced” or dictated or prescribed from above — it naturally self-emerged in ever-widening connection, interconnection, and interdependence, the same type of relationships I observed in Nature’s Web.

Natural systems develop as a series of nested holons as you may remember, everything is a part/whole up and down a great chain of being, with Cosmic Love and self-organization as the evolutionary driver toward greater complexity — rather than having an external boss having to tell people what to do.

And – to reiterate a key point – Nature is radically inclusive!

Adam Smith and the Spiritual Wealth of Nations

Through what we ended up calling the Conscious Community Network, we discovered a way to integrate intuitive, spiritual knowing with a down-to-earth, practical way to connect and amplify the good in our community.

As you will read in the “What Unites Humanity” chapter, we re-discovered the Ancient Blueprint through crowd-sourced Virtues, which provided a firm foundation for a system based on intentional mutual benefit. Above and beyond all the practical work we did to strengthen our local economy was a sense of purpose and principle.

That’s why, in some of the first meetings, we had public discussions about how profound and important Adam Smith's ideas were—it turns out the “father” of the “free-market” idea was passionate about ethics, morality, and spirituality. Prior to his famous Wealth of Nations, his lesser-known first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, described the underlying principle behind all healthy societies and economies as “universal fellow feeling” — known more commonly as the Virtue of empathy.

Smith grew up in a small town in Scotland during the early 1700s and observed what we now would call a local farmer’s market. He watched how people, buyers, and sellers exchanged goods, services, and gossip! He saw first-hand how individual freedom of action, based on trust and empathy, and the morality underpinning it, is key to any successful society.

I resonated with that perspective.

Adam Smith described morality as being rooted in a divine Providence, a Natural Law -- I would call it the Logos -- imprinting human beings with an innate moral sense that allowed them to treat each other in a way that benefited themselves and society at the same time. He felt that people would naturally seek out ways to achieve their own ends by becoming “mutually the servants of one another” and thereby would benefit others even as we seek to benefit ourselves.

Also, according to Adam Smith,

“How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

This Adam Smith clearly bears no resemblance to the narrative you hear from many “right-wing” conservatives or libertarians who claim that they are the true champions of “capitalism” and “free markets” OR “left-wing” Progressives who claim to be anti-capitalist or “post-capitalist” — whatever that means.

Both “pro’” and “anti-“ capitalists are missing the point. First, the cherished “capitalist” idea of “free market” and the “invisible hand” is a self-serving fiction. That “invisible hand” was all but invisible in Adam Smith’s writings – it is mentioned only three times. Just as surely as Darwinism became “social Darwinism” as an excuse to blame the lower classes for their status, Smith’s work has been distorted to “if we all acted in our selfish interest, that somehow that would lead to the greater good!”

The anti-capitalists, meanwhile, through whatever “ism” they put forward—communism, socialism, collectivism—are simply instituting another dominator system, as in “meet the new boss, same as the old boss.” The Culture of Separation goes hand in hand with domination — and it is thousands of years old, part of the larger development of the “materialist” worldview, prior to any of the modern economic theory “isms.”. Whether the many are dominating the few or the few are dominating the many, it is a battlefield situation.

On the new playing field of Symbiotic Kinship, personal benefit and serving the public good are not mutually exclusive - they are one and the same. As I mentioned earlier, many leaders may join these Symbiotic Networks first acting on what we have called “enlightened self-interest,” but the network initiators like me and the core group really did follow Adam Smith’s deeper meaning of Virtues being the foundation for any society or economy.

Another reason the pro or anti-capitalist ideologies are just an irrelevant distraction is that “capitalism” in any pure sense doesn’t really exist!

We seem to be living in a system more clearly defined as global “corporatism” that has spawned a global oligarchy—where large companies have all but merged with national and global political players to call the shots over our lives and future from the top down. In recent years, it has become clear to me how many on the “left-wing” and regenerative and other “new economy” activists claim to be anti-capitalist, post-capitalist, or anti-free markets and sometimes even anti-private property.

Instead, they promote either big government regulation or collectivist solutions, which, because of their own top-down approach, can be just as oppressive as the system they are fighting.

Others gravitate toward local solutions like unions, consumer—or worker-owned cooperatives, credit unions, public banks and utilities, trusts, regenerative enterprises, neighborhood corporations, mutual aid, bartering, gifting economies, or some form of public ownership. But too often, these ventures may be burdened by—and captured by—political movements around ideological terms involving “social justice,” equity, gender, or race.

So, why am I making this point? And why am I making it here?

Because over the past decades, well-intentioned movements for a more just and humane economic and social system have been identified with a specific political ideology and, consequently, have been “captured” without even knowing it. As a result, there are hidden assumptions that are tacitly accepted as true so as to fit that political sensibility and ideology. For example, there is an assumption that capitalism is “bad,” and so collectivism must be “good.”

If we are to be true UNITERS and not DIVIDERS, we must not accept “this vs. that” assumptions but rather be curious as to how each perspective brings some element of the truth. This is not to “make nice” or pretend there are no divisions or disagreements, but rather to recognize that every “ism” is ultimately on the battlefield against some other “ism.” While these “absolute” views might sometimes be a helpful place to come from, they cannot take us where we want to or need to go – they cannot uplift us beyond our silos.

That’s why universal Virtues – that transcend not only religious perspective but the artificial and divisive categories of “left” and “right” – are the foundation for the Culture of Connection that will connect and amplify the good and bring about a truly “virtuous economy.”

Virtues call forth the Culture of Connection, which is when we unite around a common purpose and well-being. Paradoxically, when we focus on the symptoms of the Culture of Separation – whether we see the “culprit” as capitalism or collectivism, racism or wokism, or any other ism – we actually accentuate and amplify the division itself.

We end up wasting energy fighting against what we don’t like and using only a fraction of our time building the alternative beyond any of the political divides.

I want to go back to something I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter (the previous post), where I listed twenty-five “new economy” movements with their own ideologies and siloed communities.

At the same time, I have identified a “counter-trend” – awakening individuals and forward-seeing organizations that seek to weave the threads of what they have developed into a whole-cloth movement. Our experience in Reno – and, of course, Sarvodaya – calls on us to join in a common cause, step outside of the comfortable silos, and build bridges to local Main Street businesses and organizations.

It would be an “all species” movement that includes everyone in a local community who desires a new Culture of Connection. ALL local organizations—“conventional” enterprises AND “new economy” initiatives—would be brought together to build what I have previously called a “Network Commons” (more on this later).

That is how we truly, in the real world, build a virtuous economy using our

“spiritual wealth” as the Power to UNITE the Good and do that locally, wherever we are.

Find out more about building Regional Economies in the NEXT POST — Chapter 6, Part 3: Regional Economies – a Virtuous Free Market…“Spiritual Capital” – The Key to a Virtuous Economy

PREVIOUS POST

TABLE OF CONTENTS

NEXT POST

I note you mention Amazon and online stores. Yet you do not mention how they can or if they should be included. Think of a bookshop that is a bricks and mortar store - easily seen as a local business. CONTRAST it with a clicks and collect place - is it a local business? How do you deal with the latter if they have an Amazon or e-Bay listing AND only such a virtual listing? BE good to get some ideas on what your concshy network did and think about this.